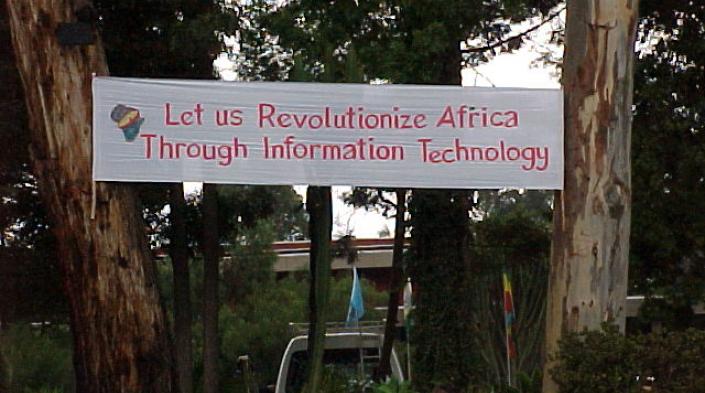

Photo provided by Mike Jensen and published with permission.

This piece was inspired by an APC article entitled “Mike Jensen: The pre-internet days [1]“. This post was originally published [2] on Association for Progressive Communications (APC) News and is part of a partnership between APC and Rising Voices.

In the early 1980s, before the internet as we know it existed, groups of activists from different corners of the world were working on stand-alone systems with “human gateways”. Technicians had to physically travel from one part of the world to another to install software and programme code to allow different computer systems to communicate with each other and share information.

Environmental awareness and social justice were at the core of these initial connectivity efforts, with pioneers such as Mike Jensen (recently inducted into the Internet Hall of Fame [3]) immersed in the anti-Apartheid and environmental struggles. As Jensen explained in a series of interviews with Brian Martin Murphy [1]:

We were immersed in a social movement. The political ambition was to make use of these new tools to further the general goals, which were initially focused on the environment. We were using ‘The Web’ as a way of connecting organisations, and supporting them in whatever they were doing.

In Canada, Jensen had set up an early networking system in the mid-1980s which he called “The Web [4]“, named at a time before Tim Berners-Lee [5] called his invention the “World Wide Web”. In one of his first installations, developed with support from a Canadian environmental NGO, Jensen created a multi-user network by installing a version of Unix on a cheap personal computer. Non-governmental organisations now had access to an inexpensive alternative to commercial mainframe timesharing systems, and this attracted many more active users. Due to its success, there was demand to replicate the set-up at other organisations.

Other initiatives in the United States and the United Kingdom were creating similar networks for use by NGOs, which led to the creation of the Association for Progressive Communications (APC). This early iteration of APC involved a team of technicians that worked alongside with local technicians to install software and networks to connect NGOs in both the developed and the developing world.

The early wireless cards activists used, before laptops had built in WiFi. Photo provided by Mike Jensen and used with permission.

The anti-Apartheid struggle and early connectivity in Africa

During the 1980s, the workers’ struggle in South Africa was inextricably linked with the struggle against Apartheid. International solidarity with South African labour unions was part of a broader solidarity campaign with liberation movements in the region. Through its links with the labour movement in the United Kingdom, Johannesburg-based NGO Labour and Economic Research Committee (LERC) made contact with the Poptel group in Manchester that was using email through a commercial provider in Germany called Geonet. In early 1988 a steering group was convened to involve progressive “service organisations” (at that time the term NGO was unknown in South Africa) outside the labour movement.

At the height of state repression of the democratic movement in the 1980s, labour and religious organisations were the only explicitly anti-Apartheid institutions that were able to operate on the ground. They were also part of international networks and therefore predisposed to making use of emerging electronic communications to sustain these networks. Soon the most active users of these communications were journalists and political activists, relieved to have found a way of getting information in and out of the country easily and quickly.

Former APC executive director Anriette Esterhuysen recollects her anti-apartheid work in those pre-internet times as follows:

Part of my work at the Ecumenical Documentation and Information Centre for Eastern and Southern Africa was to organise training workshops in documentation techniques. I collaborated with a Rome-based NGO, the International Documentation Centre (IDOC). Through IDOC I made contact with Interdoc, and in December 1987 a Dutch Interdoc member came to Zimbabwe and demonstrated the use of modems and email at a workshop. Subsequently we included email and modem training in all our workshops. We supplied our group with modems, and astonishingly, at least 5% managed to stay connected using long-distance modem-to-modem connections until, by the early 1990s, they could use the far easier and cheaper Fidonet networks established through the Economic Commission for Africa, the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and APC.

Early 1990s

By the end of 1991, Jensen, with assistance from colleagues in the APC network, had helped knit together seven nations into the APC network, including Senegal, Nigeria and Kenya. Each node of the network linked activists and NGOs in each country locally, nationally and internationally. This was a feat in itself and even more so considering that most of the newly linked-up groups were in Africa, where the internet would be long in coming and expensive when it arrived.

Mike Jensen's kit bag with the various modem cards, cables and telephone line adaptors needed to maintain connectivity during travels in Africa. Photo provided by Jensen and used with permission.

In 1997, Jensen said in an interview with APC [1]:

What motivated me to spend the last ten years spreading access to the network is that I’ve always felt that there was not much point in having the content there if a lot of people can’t use it. We are slowly getting there. The internet is beginning to pervade, and capital cities of Africa now at least have some degree of access, but that’s not good enough yet. We still have to bring it further out so that people in rural areas have access.

Two decades later, the reach of the internet has progressed to a point that many may not have imagined. However, the potential for linking people through technology that showed signs of promise during those early days is not yet completely fulfilled, observes Jensen. “Only half the world has any form of internet connection at all, and many marginalised groups continue to be excluded.” But with advances in technology continuing to make it less costly to connect remote areas, and new models of connectivity self-provision becoming increasingly common, the prospects for better access and sharing of knowledge online are improving. Jensen, and many others, continue their work on expanding human rights by helping to link people.