“Violence was the concept in dispute”

Reframed Stories asks people to respond to dominant themes in news coverage about themselves and the issues that affect them. The stories center on the reflections of persons who are more often represented by others than by themselves in media.

Apawki Castro is the elected leader of communications for the Confederation of the Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) for the 2017-2020 period.

Me parece interesante considerar las palabras asociadas con violencia en relación al conflicto de la nacionalidad Shuar porque fue uno de los conceptos que de lado a lado quisimos posicionar. La violencia fue el concepto en disputa y eso demuestra esta gráfica.

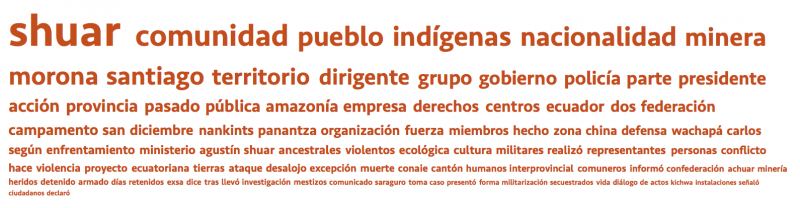

I think it is interesting to consider the words associated with “violence” related to the conflict with the Shuar nationality, because it was a term that every side tried to claim or define. Violence was the concept in dispute, and I think this graphic shows that.

Dominant words from 697 articles published between May 2016 and June 2017 found mentioning “shuar” within four Media Cloud collections of Ecuador’s Spanish-language media outlets. (View original query; View larger image)

Por nuestro lado, nosotros intentamos posicionar la noción de que la violencia provino y proviene del Estado, a través de todas las concesiones mineras y de todo el atraco en los territorios.

Nuestra intención también ha sido recalcar otros temas importantes para nosotros – como el tema de la identidad, las tradiciones y la cultura – y desde ahí construir un análisis coyuntural y de posiciones políticas, pero no veo el tema de identidad cubierto en los medios, como tampoco lo veo en esta nube de palabras.

From our end, we tried to position the idea that it was the State that generated violence through all the mining concessions and the attempts to take over the territory.

Our intention has also been to highlight other topics that are important for us – such as identity, traditions, and culture – and build an analysis more related to current events and political positions from there. However, I don’t see the topic of identity covered by the media and I don’t see it in the word cloud either.

National Indigenous Youth of Ecuador Camp – The Children of the First Uprising – in commemoration of the 25th Anniversary of the First Indigenous Uprising. Published with permission of the author.

Por otro lado, todo el poder mediático que tiene el Estado ha intentado satanizar a los hermanos y hermanas Shuar, hacerles ver como unos salvajes, unos violentos, unos incivilizados. A partir de esa comprensión colonial, el Estado intentó posicionar la idea de que los hermanos de la nacionalidad Shuar fueron los generadores de violencia en los acontecimientos que ocurrieron en diciembre del año 2016. Es decir, intentaron responsabilizar a la nacionalidad Shuar de todo el acontecimiento en el campamento la Esperanza, en Nankints.

Debemos tener la capacidad de interpretar el poder mediático con la que actúa el Estado en estos casos en los que, en gran parte con el apoyo de los medios, pretende difundir la idea de violencia a nivel internacional vinculándola a lo salvaje y a la barbarie.

Tenemos que posicionar la interrogante desde los espacios alternativos, populares y comunitarios de quién es el que violenta, y desde dónde proviene la violencia, ¿desde el Estado o los pueblos y nacionalidades? ¿Es generar violencia el hecho de defender los territorios ancestrales de las grandes empresas mineras, petroleras e hidroeléctricas? ¿Acaso despojar a los pueblos y nacionalidades de sus espacios de vida no es violencia? ¿Militarizar un espacio comunitario, colectivo con autodeterminación, no es violencia?

Desde el Gobierno nacional militarizaron un territorio habitado por la nacionalidad Shuar, por el simple hecho de defender a la empresa minera china que operaba ahí. ¿Es obligación del Gobierno defender a sus habitantes o a las empresas transnacionales? Este tipo de interrogantes son las que debemos explorar y analizar a profundidad.

On the other hand, all the media power from the State has tried to demonize our Shuar brothers and sisters, trying to depict them as savages, violent, and uncivilized. Starting from that colonial way of thinking, the State tried to position the idea that the Shuar nationality was guilty of generating the violence that took place in December 2016. In this way, it tried to blame the Shuar people for all the conflict that took place in the Esperanza camp in Nankints.

We need to interpret the media power that the State exercises in these cases where, supported to a great extent by media, aims to promote the conception of violence at an international level linking it to savagery and barbarism.

We must question this idea from alternative and community spaces. We must ask who is the violent part, and where the violence is coming from. Is it coming from the State or from the people? Is defending the ancestral territories from the big mining, oil, and hydro-electric companies actually a generation of violence? Isn't it violence to expropriate indigenous peoples from their spaces of life? Isn't it violence to militarize a community or collective space with auto-determination?

The Government militarized the land where the Shuar people has always lived just to defend the Chinese company that operated there. Is the role of the State to defend its own people or transnational companies? These are the types of questions we need to keep exploring and analyzing in depth.

This is part of a series developed in close collaboration with the indigenous community of Sarayaku and the Shuar nationality, both situated in the Ecuadorian Amazon region. The Sarayaku and Shuar people have held long fights at a national and international level to stop extraction projects in their territories, and public messaging has been an important part of this struggle. We asked members to respond to some preliminary media analysis that suggests how topics related to their communities are represented in news.

Support our work

Since Rising Voices launched in 2007, we’ve supported nearly 100 underrepresented communities through training, mentoring, microgrants and connections with peer networks. Our support has helped these groups develop bottom-up approaches to using technology and the internet to meet their needs and enhance their lives.

Please consider making a donation to help us continue this work.