Elmo Bautista and his late father Espíritu Bautista digitally record words in the Yanesha language of Peru during a workshop organized by the Living Tongues Institute. Photo by Eddie Avila and used with permission.

Welcome to the inaugural edition of DigiGlot, a bi-weekly collaborative newsletter that reports on how indigenous, minority, and endangered language communities are adopting and adapting technology to increase the digital presence of their languages, and in the process changing the internet landscape by increasing linguistic diversity online. This collaborative publication will be compiled by a team of volunteers. The contributors will be listed at the bottom of each issue.

As this is our first issue, we expect that the format and the content of DigiGlot will evolve over the next few months. We’re always looking for reader feedback as well as suggestions for items to be included in future editions. You can get in touch with us through the Rising Voices contact page.

[toc]

Tech and digital activism on the roster for the International Year of Indigenous Languages

With the arrival of 2019, the International Year of Indigenous Languages is officially underway. Back in December 2016, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed 2019 the year for an awareness campaign coordinated by UNESCO and focusing on five areas, including capacity building and increasing international cooperation. A consortium of language-related organizations is being formed to highlight the campaign on social media using the hashtag #IYIL2019. As an additional component of the campaign, UNESCO announced a call for research papers, with one of the key topic areas being “Technology, digital activism, and artificial intelligence (e.g. language technology).”

Are “extended” Latin characters slowing the growth of African Wikipedias?

One of the immediate legacies of European colonialism in present-day Africa is a disjointed patchwork of writing systems for local languages. While many African languages have been written using the Latin alphabet for several decades, languages have varied greatly in their use of special and accented letters, or the “extended” Latin characters. Some languages were even written differently on either side of national borders. In this series of essays [parts 1, 2, 3], Don Osborn reflects on four decades of African language standardization and explains how early decisions about orthography may have consequences for digital media production today.

Osborn suggests that the challenge presented by using extended Latin orthographies—those that force users to work their way through unstandardized input interfaces to type the “special” characters in their language—may be limiting the development of some African Wikipedias. His analysis finds that African Wikipedias “written in extended and complex Latin hav[e] on average about a third the number of articles” as those Wikipedias written in a simpler Latin alphabet. While Osborn acknowledges that his analysis is preliminary, his observations usefully highlight some of the complexities of building digital ecologies in local languages.

Wikipedia's Universal Language Selector adds three West African languages

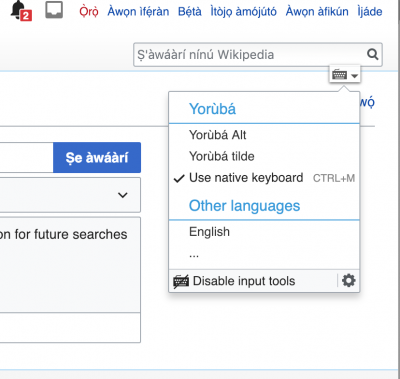

Ayokunle Odedere is a Nigerian Wikipedian and coordinator of the Wikimedia Hub in Ibadan, Nigeria. He organizes and mobilizes activities and campaigns such as the recent AfroCine project. Working on Wikipedia, Odedere noticed that both new and experienced editors were having trouble typing the necessary diacritical marks in Wikipedia articles for national languages such as Yoruba, Hausa, and Igbo.

While there are special keyboards such as the Yoruba Name keyboards for Mac and Windows and other virtual keyboards that allow users to display these special characters, they require some degree of technical knowledge to install and utilize. Odedere envisioned a solution built into Wikipedia itself. He put in a request on the Wikimedia Community Wishlist to have Yoruba, Hausa and Igbo incorporated into the Universal Language Selector (ULS), a facility available for Wikipedia and other Wikimedia projects to “allow users to type text in different languages not directly supported by their keyboard, read content in a script for which fonts are not available locally, or customize the language in which menus are displayed.” The request was granted and the Wikimedia Foundation Language Team included the three West African languages in the ULS. Now Wikipedia editors using a desktop or laptop computer can incorporate the special characters into their texts by typing the tilde (~) character before the corresponding letter.

While there are special keyboards such as the Yoruba Name keyboards for Mac and Windows and other virtual keyboards that allow users to display these special characters, they require some degree of technical knowledge to install and utilize. Odedere envisioned a solution built into Wikipedia itself. He put in a request on the Wikimedia Community Wishlist to have Yoruba, Hausa and Igbo incorporated into the Universal Language Selector (ULS), a facility available for Wikipedia and other Wikimedia projects to “allow users to type text in different languages not directly supported by their keyboard, read content in a script for which fonts are not available locally, or customize the language in which menus are displayed.” The request was granted and the Wikimedia Foundation Language Team included the three West African languages in the ULS. Now Wikipedia editors using a desktop or laptop computer can incorporate the special characters into their texts by typing the tilde (~) character before the corresponding letter.

Modernizing Hawaiian-language text with the push of a button

The Hawaiian language has a long tradition of writing, with more than 125,000 newspaper pages published in the 19th and early 20th century. Unfortunately, most of that text was written in an orthography devised by missionaries which, unlike the standard modern orthography, doesn’t fully reflect the sound system of the language. This means that these older texts are both difficult to read for today’s speakers, and also cannot readily be used for training natural language processing systems. This paper, by researchers at the University of Oxford and Google Deep Mind, describes a system that combines so-called “finite state transducers”, a well-known technology in the field, with deep learning to develop a system for automatically modernizing Hawaiian texts. This approach could possibly be applied to the numerous other languages which have undergone orthographic changes or standardization.

Will Siri and Alexa speak Welsh someday?

The Welsh government's Welsh language minister Eluned Morgan has asserted the importance of smart speakers and voice-driven devices such as Alexa and Siri accommodating speakers of the Welsh language. This goal is part of the government's Welsh Language Technology Action Plan, which was launched on October 23, 2018.

The plan recognizes the role that technology plays in everyday life and the importance for Welsh speakers of being able to use their language when using technology: “We want people to be able to use Welsh and English easily in their virtual lives at home, in school, in work or on the move.” The Welsh Technology Language Act recommends the development of artificial intelligence so that machines can understand spoken Welsh, and the improvement of computer-assisted translation, as part of the government's wider aim of having a million Welsh speakers by 2050.

Voice recognition technologies help to document the Seneca language

A team of researchers at the Rochester Institute of Technology in the United States is developing voice recognition technology to assist with the documentation and transcription of the Seneca language. Seneca is an endangered Native American language spoken fluently by fewer than 50 individuals, hence the urgency of documenting and preserving the language. As recording and manually transcribing speech is expensive and time-consuming, researchers are seeking to exploit voice recognition technology to assist with this task.

Voice recognition is a technological process that recognizes the sounds produced by the human voice and transcribes them automatically into written form. Develop voice recognition systems for languages with few sources of data is a challenge, as these systems requires a large amount of data to “train” them to recognize the language. For this cutting-edge research the team was awarded $181,682 over four years by the US National Science Foundation.

Upcoming Events & Opportunities

- The Endangered Languages Program is partnering with the Language Documentation Training Center (LDTC) to offer a free weekly webinar series on language documentation in February and March 2019. Those interested can sign up using this form.

- The Endangered Language Fund’s 2019 round of Language Legacies grants is now open. These grants offer up to $4,000 USD (on average around $2,000 USD) to support language documentation and revitalization efforts around the world. Prospective applicants do not require an academic background. The application deadline is March 15, 2019.

- The PULiiMA 2019 – Indigenous Languages & Technology Conference scheduled to take place in Darwin, Australia on August 19-22, 2019 has launched its open call for presenters. The submission deadline is February 9, 2019.