Rising Voices (RV) is partnering with the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) [2] which produced the 2018 Global Information Society Watch (GISWatch) focusing on community networks defined as “communication networks built, owned, operated, and used by citizens in a participatory and open manner.” Over the next several months, RV will be republishing versions of the country reports highlighting diverse community networks from around the world.

This country report [3] was written by Andrew Garton [4] of Media and Communications, Swinburne University of Technology [5]. Please visit the GISWatch website [6] for the full report which is also available under a CC BY 4.0 license.

It was a Thursday winter evening in Melbourne. Around 30 or so people had either walked from nearby tram stops or pedalled across the city to Toy Satellite's [7] two-story warehouse in North Fitzroy. Some, their faces lit by open laptops, were using Netstumbler [8] to find us. We had emailed GPS coordinates and the name, or SSID, of our now freely open wireless hub. The more intrepid would use our network's signal strength to get them to the front door. It was 11 July 2002 and everyone was gathering for the launch of TS Wireless, a joint project with London-based Free2Air, a free community wireless network. The plan was to stream royalty-free music produced by local artists 24 hours a day to anyone within a three-kilometre radius. It took around 48 hours to have our server hacked and the whole operation halted! But it started off great!

In the beginning we shared

In the beginning BBSs, or Bulletin Board Systems, were the earliest publicly accessible computer, the first one known to have gone online in Chicago in the United States, on 16 February 1978. The Computerized Bulletin Board System (CBBS) [9] was based on software written by Ward Christensen and Randy Suess, considered the fathers of public access networks. The internet’s precursor, ARPANET [10], was still in its infancy. People would dial in to BBS computers, exchanging software, documents and graphics. Data rates were slow at the time, commonly 300 characters per second, and modems were devices known as “acoustic couplers” which were mounted onto telephone handsets; the ear piece would receive data while the mouthpiece would send it.

Individual BBSs were the earliest equivalent of a website, each supporting communities of common interest. Perhaps the first BBS style of network established for artists was Robert Adrian X's ARTEX [11], an electronic mailbox for sharing ideas and organising intercontinental telematic artworks. A Canadian who spent his entire adult life in Vienna, Adrian X had pioneered politically charged artistic practices within electronic and broadcast networks. ARTEX foreshadowed “store and forward”, the share and copy potential of the future internet. It was a kind of precursor to the ubiquitous Dropbox, a micro-cloud storage utility when clouds still hung in the sky. It was cheap too, costing artists a few cents a day for data storage only.

By the 1990s the internet was well underway, and artists were not only wanting to share: they were being found. I held the view that an increasing number of people began looking for music beyond radio and music stores. There was plenty available if you knew where to look. The global reach of the internet meant it was easier to share far more music than anyone could possibly hear, and so much more than anyone had ever heard on a radio or found in music shops. The problem, in my opinion, was not piracy that would afflict the music industry, it was diversity. There was so much more diverse music and so many artists appearing online than there would ever be on any of the industry charts listing the 100 most popular recording artists of the day – the measure by which royalties were not only dispersed, but guaranteed.

We saw an opportunity. How could we share all this independently produced music to people who didn’t know where to look for it? How could we make this happen legitimately and accessible to anyone for free? No sooner had we published a white paper describing TS Wireless than we found a partner in the London-based wireless network host, Free2Air [12]. Enthusiastic about our project, they arranged for an aerial antenna and several metres of specialised cable to be shipped out to us. Things were moving quickly. Now we had to find a server, the technical nous to pull it all together, and permission from the body corporate to mount an antenna onto the roof of the building. There was no shortage of music to share, no shortage of skills to make it happen and a whole lot more to learn. TS Wireless was underway!

Streaming music locally

By 2002 streaming audio had become easy, video less so. However, streaming anything over wireless was still in its technical infancy. With the help of an international network of open source software developers and visiting and local Wi-Fi expertise, we gave it a good, decent, thoroughly robust crack. But before we had the server up and running we encountered our first and most challenging problem.

The royalty collection agency

The original plan was not to stream ambient music – which we ended up doing – it was to share locally produced music in all its myriad forms. Along with Free2Air, we wanted to make bandwidth a community concern, not a commercial one; we wanted to make access to local music a community concern, not a commercial one. We wanted to share our infrastructure to offer local households and businesses access to music that had yet to find an audience. We wanted to create an online community that could evolve around its own interests with music as the fire around which we would gather. But to do so we had to pay a licensing fee to the Australian Performing Rights Association (APRA). We immediately saw another opportunity. APRA did not.

Around 2000/2001, on behalf of their member composers, authors and songwriters, APRA expanded its performance licensing usage to encompass any venue in which music was publicly heard or performed. This included hair salons, cafés and many work spaces. Even Toy Satellite received a notice from APRA urging us to pay an annual fee for any music we played in our studio. Internet service providers (ISPs) were not immune from such fees either. Any music stored or streamed online was considered a public performance of said works.

We contacted APRA and asked how we could list any of the music heard over TS Wireless so that artists would be paid royalties. If we were to pay an annual performance licence fee, surely we could submit a playlist ensuring all local artists, their own members, would have royalties distributed to them. They replied stating they had not the means to do so. APRA, a national royalty collection agency with an annual turn-over in the millions, did not have the means to allocate royalties to any of the artists being played in any of the venues nor streamed from any ISP being charged an annual performance licence fee. Wow! So, who does? The answer was simple. Royalties are distributed to the popular artists of the day on the assumption that most, if not all music being heard would be popular music; otherwise it wouldn’t be popular. That meant that a small number of artists were the beneficiaries of most of the performance licence fees whether they were heard in any local café, which they were not, or streamed over TS Wireless, which they absolutely were not.

We offered APRA an opportunity.

We were prepared to share with APRA all TS Wireless playlists. We would even write software to email them the playlist in a form that could be imported into their database or spreadsheets. These playlists would be filled with all sorts of fascinating metadata, enabling APRA to apportion royalties to all local artists on our server. That’s all artists.

APRA replied stating they did not have the means to interpret that data into meaningful outcomes for artists legitimately being heard on our servers nor in any of the venues that would sign to TS Wireless. We had considered adding a feature where custom playlists created by TS Wireless subscribers could be sent to APRA. But given APRA could not make use of this information, no matter what form it could be sent to them in, we had to consider our options. How do we proceed with TS Wireless knowing the music we would have to pay APRA the rights to stream would not result in any additional royalties to the Melbourne music makers we would host?

It was at this point that we decided to only stream generative, ambient music for which APRA had neither the means to register it as being “composed” by anyone, nor an argument to warrant a performance licence. In short, music that was constantly changing was not in APRA’s interests to have on their books. Our generative pieces were works that were never heard the same twice; some of them were hours, days and even weeks in length. APRA did not have the means to support such original works no matter how they were composed nor by whom. Even before we got underway, we knew an audience for generative ambient music would be limited. We forged ahead nonetheless.

The team

Visiting Australia at the time was Spanish-born Alberto Escudero-Pascual, who brought with him extensive wireless networking expertise. He had the technical skills and real-world experience and he grew fond of Melbourne, often saying it was the first place he had visited where no one asked where he had come from. At the time Alberto was an associate professor at the Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden, where he was completing a PhD in mass electronic surveillance systems. Alberto knew a thing or two. He also knew how to modify Orinoco network cards so that they would converse with Linux operating systems.

Remote expertise came in the shape of the quietly spoken Adam Burns, who once told me it was through the study of high mathematics that he had come closest to God. Adam was the founder of Free2Air and had worked with me at Pegasus Networks, Australia’s first publicly accessible ISP.

Our local team included web coder par excellence Justina Curtis. Justina wrote up most of our documentation, coded our front-end and hosted with unyielding generosity the many late nights it had taken to construct the entire project. Justina brought expertise in training in information and communication technology (ICT) media literacy, and interaction and accessibility design. She was also a co-founder of Toy Satellite. Every project needs a social binder and Justina was ours.

Supporting us all with no end of bad jokes, rigorous system administrative skills and an ability to work insanely long hours and remain not only focused, but thorough, was Grant McHerron. Both he and our in-house technical director, Bruce Morrison, were determined to not let any problem impede them. Bruce had also worked with me at Pegasus Networks and, like Grant, had the gift of tolerance and fortitude. It is impressive to see people work at problems as if they were puzzles, applying game theory within their deliberations. Another member of our team was Linux aficionado Dennis McGregor. I can’t recall much about Dennis other than the long hours we spent together stitching the entire project together with good humour and collaborative ease.

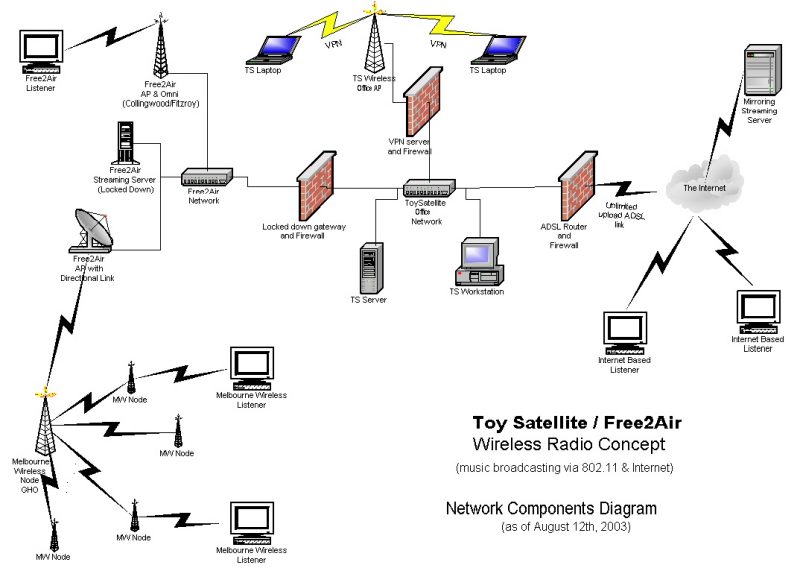

Prepared by Grant McHerron (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International).

Network design

TS Wireless was accessible from within a three kilometre radius of our 2.4 GHz omnidirectional aerial mounted on the roof of our studio in North Fitzroy, Melbourne. We made use of the full capacity of the aerial, which provided the most extensive coverage for the technology available at the time.7 Yes, we did get permission from the body corporate to climb over the top of several premises. We made sure we could provide maximum line of sight to all participants. This included local members of Melbourne Wireless [13], arts practitioners (the Melbourne Fringe Festival had their office space nearby), our neighbours and random visitors.

The antenna was mounted to an existing television aerial with U clamps. Waterproof electrical tape was used to insulate the connection between the cable and antenna mounting. Thirty metres of heavily insulated cable was wound around the perimeter of the roof and into the building through a rear window where it was plugged directly into Hermes, our wireless server. Hermes also administered an ADSL connection to our broadband provider as well as a firewalled gateway to the internet.

Hermes was installed with a basic setup of Mandrake Linux. We used Firewall Builder [14], an open source application, to create and manage the firewall, and X-Windows from which non-tech team members could run diagnostics tools such as KOrinoco [15] to generate signal strength charts. A second server, Yuri, was set up to run the generative music software, SSEYO Koan Pro.

For streaming we used ffserver [16] and FFmpeg [17], the latter for its ability to do on-the-fly encoding to multiple formats concurrently, thus avoiding being bound to platform-specific, or rather, biased codecs. FFmpeg does capture and encoding and then outputs to ffserver and/or to file(s); ffserver then provides streams to clients connecting over a network. Due to limited resources and the heavy processing demands of multiple format encoding, we chose to use the MPEG codec for both audio and video.

We encoded two MPEG streams, one of a high quality, and another of a lower quality for those with less bandwidth. The encoder component of FFmpeg had the ability to output to multiple destinations, so we sent one stream to a local ffserver, to an ffserver in Sweden, and to a hard drive for archival purposes.

Free2Air.org had also mirrored our two MPEG streams – or MP2 stream – by running a client from the server in Sweden and then re-serving it over an Icecast [18] server in London. A web server threw up a web page for users who would find a link to the live audio stream, with FAQs and a contact form. It was pretty much a BBS with internet server software and hardware. It was a private internet. It had all the features of the internet without the reach to it. This was a useful backup to our wireless streaming experiment, because, at the time of deployment, it was illegal to provide access to the internet from a wireless node, that is, piggy-backing off a commercial ADSL provider. The Australian Communication Authority regulated all spread spectrum radio communication, including the 2.4-2.4835 GHz radio-frequency band our wireless network would operate in.

TS Wireless on air

Back at the launch, curious and eager, everyone was invited to have their hands scanned as they entered the building. These were hurriedly compiled into a video and projected as large as we could possibly make it onto the interior walls of the Toy Satellite studio at the moment TS Wireless was officially launched. Adam Burns was video streamed live from London gifting us with his wisdom, describing access to free and reliable bandwidth as a fundamental right. Alberto Escudero-Pascual concluded the evening with an impassioned appeal for community as the locus of new ideas, what artist Brian Eno describes as “cooperative intelligence. [19]”

Once up and running, at our peak, TS Wireless supported 50 simultaneous users. We have no idea who these users were. We had no need to know; but we knew audio streams were frequently served.

This was after we had secured our servers ensuring they had no internet capacity whatsoever. Initially we had an internet connection via a local ADSL provider. This meant we could have our audio streams mirrored by servers anywhere in the world, including Free2Air. But if you recall, dear reader, within 48 hours of our launch we had been hacked. In short, someone had literally sat in a car opposite the studio and pulled gigabytes of data through our internet connection. It nearly sent us broke. Australia has some of the most expensive broadband charges on the planet. If we breached our cap, which we had after our launch, we were charged for every single byte of data that moved across it. We learned that if someone wants bandwidth badly enough they will come with every means at their disposal to nab it.

A second location was proposed by a small business in a neighbouring suburb where we could trial a semi-commercial operation amid shopkeepers. Every shopkeeper had been approached by APRA to pay that annual licence fee. As such, many were keen to see local music makers benefit from this expense. TS Wireless provided a model many were keen to subscribe to.

Smith Street Wireless was to launch in 2004, but yet again APRA was unable to work with our playlists. Subsequently no one would subscribe to Smith Street Wireless if licence fees paid to APRA did not result in royalties to local artists. Smith Street Wireless was doomed.

Reflections

We didn’t bridge any digital divide, we didn’t fill a development void nor provide critical information where it could not otherwise be reached. We experimented with a new idea to find that no one was particularly interested in a perpetual music streaming service. Free too! Portable MP3 players were as commonplace then as smartphones are now. Most people we knew were content with curating their players.

There was also no interest in the metadata we offered to share with royalty collection agencies, in spite of all the public spaces, businesses and venues paying annual performance licence fees. This left independent music makers with fewer means to accrue royalties in a marketplace adapting to new technologies. But we did, as we had done so many times prior, find that the community we had sought to nurture had been with us all along.

The community that preceded the network

TS Wireless may not have sustained an online community for more than six months, yet there was community around us, tweaked by a crazy idea all along. It was there, and still exists, through the network of software developers, web coders and designers, passionate wardrivers and NetStumbler aficionados. These are the people we rarely see, who had created some of the more experimental and wildly innovative networks of their time. We had worked in remote villages in Africa, Southeast Asia and Indochina. We provided training and advice to regional and rural telecentres in Australia, including creating some of the earliest websites for community groups, non-government organisations and small businesses in the country. We had, at personal expense, established the means for anyone interested to learn about wireless networks and how they may foster community, belonging, nurturing curiosity and innovation where it may otherwise languish. Our experiment may have failed on paper, but it succeeded in bringing together a group of people who shared an experience that we had all grown from, and the ripple effect of that gathering expands still.

Epilogue

Sixteen years since TS Wireless rose and stumbled, APRA draws annual performing rights fees from hotels, pubs and taverns, restaurants and cafés, fitness centres, numerous work spaces such as doctors’ and dentists’ surgeries, corporate reception areas, service stations, salons and nightclubs, motels and other forms of accommodation. They have special licences for skating and ice rinks, community bands and choirs, recreation and leisure centres, schools, universities and colleges, sporting events, local government authorities, transport systems, funeral directors and funeral providers.

APRA now applies music recognition technology described as a “digital fingerprint” [20] that each piece of music carries which is matched against a database containing the work's metadata “enabling the owners of each matched work to be identified and paid accordingly.” They still have no clear mechanism for allocating royalties from all the performance licence fees they collect from public spaces, but they do have a term for where such fees reside: “distribution by analogy”. This means that “licence fees are added to an existing distribution pool that is most similar in terms of its music content.” I’m not sure I understand what this means, but what I do know is that if any of my music is played at Frankie God of Hair where I get my hair cut, I’ll get a decent trim, but not a single cent in royalties.

What remains of TS Wireless are its antenna and cables sitting in a Melbourne storage unit. The servers Hermes and Yuri and all our wireless workstations were taken to an e‑recycling centre, the CRT monitors thrown into an awesome open bin along with routers, modems, metres of ethernet cable, keyboards, spare motherboards, and memory cards.

There was nothing graceful about this kind of closure, but there was comfort knowing that much of this gear would find reuse elsewhere.

For more information regarding action steps, further reading, and ways to get involved, please visit the full report [3] on the GISWatch website.