Photo provided by Karen Fowler-Watt.

Rising Voices note: We are opening up this space for project leaders to share the process and their approach to working with local communities to produce media that shares and amplifies local voices. This first article was written by Karen Fowler-Watt and Mat Charles.

“We learned to live with the war and likewise our land has become accustomed to it,” says Nasa teenager, Sek, as he stares at a green mountainous landscape, littered with the dead bodies of his neighbours. “There was a massacre in our community,” he goes on. “That´s when I decided to participate with the guerrilla, to defend my family.”

Sek’s story of how he became a Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia [1] (FARC for its initials in Spanish) rebel in Colombia complicates most popular and scholarly accounts of children being “forced” into armed conflict. The reality was – and continues to be – quite different.

Children often take up arms for revenge, and sometimes just for the offer of a hot meal. For A’te, Sek’s female companion, it was also about her family. The local guerrilla commander had taken a shining to her and threatened to hurt her loved ones if she didn’t go with him into the jungle. “At the time, I was 14 and I thought he was very old,” she says. “But I decided to go work with him for fear of something happening to my family.”

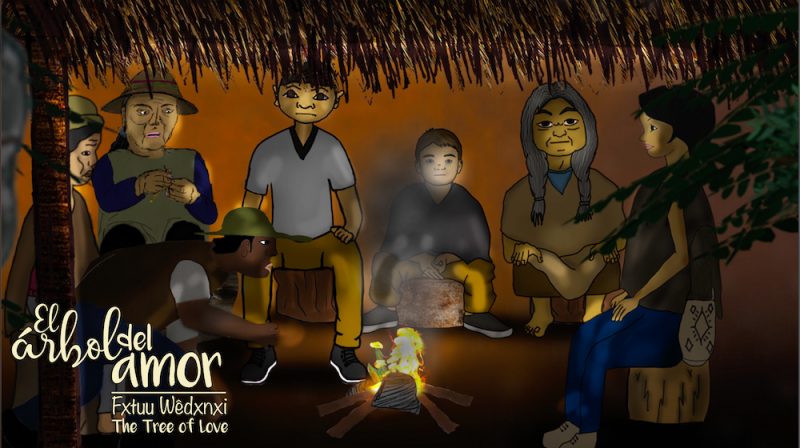

Sek (Sun) and A’te (Moon) are the main characters in the animation, el árbol del amor or The Tree of Love. The pair are fictional characters, but their stories are real, constructed from 25 testimonies elicited from former child combatants and young survivors of conflict in the remote indigenous Nasa [2] reservation of Jambaló [3], Cauca in southwestern Colombia.

Led by a team of researchers and practitioners from Bournemouth University [4], UK and in partnership with the Norwegian Refugee Council [5], and Colombian charities Fondación Fahrenheit 451 and Tyet [6], el árbol del amor is a project, funded by a grant from the UK government’s Global Challenges Research Fund, which involved a series of workshops over three months with children and young people between the ages of 9 and 24.

The decision not to use interviews as a methodological tool was key to our project. We were adamant this film would be as close to the children and young people participating as possible.

This is why it’s their voices, their stories and their animation!

We embarked on a process of what we might call ‘storylistening’. As academics and filmmakers, we became listeners and facilitators of a shared narrative space, while the workshop participants became the storytellers.

They created their own stories through the production of artefacts: drawings, poetry, and human cartography, culminating in their own animation.

Since the 2016 historic peace agreement [7] between the Colombian government and leftist Farc guerrillas, it is generally accepted in the country that journalism has a responsibility to nurture peace and can positively influence reconciliation. But most domestic media coverage of the conflict relies on government and military sources, leaving the voices of victims absent.

Javier Osuna from Fondación Fahrenheit 451 says that “the only way that journalism can work in this country is to investigate things people don’t want to hear”. Working with young people embroiled in Colombia’s civil conflict, we sought greater understanding of the suffering it can inflict through listening to their experiences of violence and forced recruitment.

El árbol del amor was created through three iterative workshops:

- Workshop I introduced the project participants to basic animation using Adobe Photoshop and After Effects. Participants experimented with various styles of animation and illustration and they also engaged in narrative and storytelling exercises to build trust.

- Workshop II focused on the development of the final script based on the initial stories from the first workshop, and completion of the storyboard according to the script.

- Workshop III concentrated on illustration and animation.

Each lasted five days. The trailer for the finished film can be seen here:

“The film uses a collage effect,” says lead animator Paola Albao. “This was the choice of the young participants. They wanted to reflect the blur of fiction and non-fiction, which is why you see animated trees and mountains, but a real river or an animated bus with real tyres that we filmed or photographed. Sure, animation offers the children anonymity, but they wanted to be sure that people would realise that this is a real story, that what we see and hear in the film really happened, and that it happened to them.”

We set out to investigate how to combine storytelling and technology to offer anonymity to vulnerable contributors of testimony, while also building narratives of empathy and immersion. The intersections between technologies, modes of visual representation, documentary, and ethnographic research offer new modes of documenting histories, lived experiences, and personal memory beyond the written word or photographic image.

Colombia’s peace of course remains fragile. Forced recruitment continues to present a major problem and the film would now be difficult to make, as the Cauca region is tense once again.

Against this background, in September 2019, the young film-makers travelled to Bogotá to screen the film and to share their stories of lived experience with the Colombian Truth Commission, which is investigating the 55 – year civil conflict. This was an important moment, as a representative from the Truth Commission told us, they are “seeking the truth of what happened to children in the conflict, their stories and their truths”.

However, this is a difficult task, rather than seeking the truth, or one truth, they hope to find sufficient truths to enable reflection. The weight of history was evident in the room: One young ex-combatant was emotional as he shared his story; he had told it before, but as he said, in this context and at this time he wanted to “get this right for my mother”, who was killed in the conflict when he was much younger. Several days after our visit, the Commission accepted the film as official testimony [8].

The project recently featured on the front page [9] of one of Colombia’s biggest dailies, El Espectador, which included a podcast [10] dedicated to the film.

Colombian Senator, Feliciano Valencia [11], who represents the indigenous Nasa community also spoke at our premiere at Cine Tonalá [12] in Bogotá:

“When we talk about conflict, we do it as journalists, academics and lawyers,” he said. “But here the young people from Cauca are telling their own story, the way they choose to tell it.”

Our hope is that this film can make a small contribution in the quest for peace and reconciliation in Colombia. The young film makers’ message, as articulated by A’te in the final scene of The Tree of Love, is clear: “I wish that through these narratives, children or adults from different places will understand what we live through, and that they won’t judge us, and that with this story, those who make war will listen to us,” she says.

Update: The full movie can be found here [13]: