‘The media should report on the water scarcity in the Indigenous communities,’ explains a young Bolivian journalist

Brisa Abapori. Photo by Jessica Peñaloza Cladera for Rising Voices.

Eleven young people from various Indigenous and Afro-Bolivian communities in the Gran Chaco region in Bolivia participated in the workshop entitled “Roipea Taperai” (“Opening Paths” in the Guaraní language). The workshop focused on the terms used in Bolivian media when reporting on climate change or Indigenous peoples in the region (you can read more about the workshop here). What follows is an interview with one of the participants from this workshop.

Brisa Abapori is from the Eiti community, located in Charagua, in southern Bolivia. She is currently studying to be a teacher, at the local Teacher College. In her free time, she actively participates in the Ñande Ñee radio station as part of the School of Indigenous Journalism.

Abapori identifies two problems related to the content in the media and on social networks about her region. The first is that the Autonomous Indigenous Government of Charagua (Kereimba Iyaambae, in the Guaraní language) continues to be referred to as a Bolivian municipality. The second is that the ravages of the drought and the fires within the Indigenous communities are not made visible. The following interview shares her thoughts.

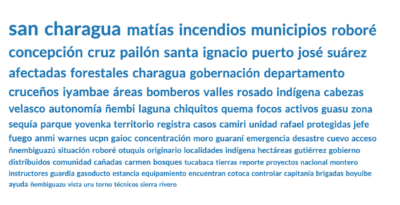

Word cloud for the terms “Charagua” generated by Media Cloud.

Rising Voices (RV): During the workshop, the participants chose a word cloud and identified some terms within it. You chose the word cloud pertaining to news coverage of the region of “Charagua” and you identified the terms “fire,” “chaqueo,” and “disaster” to focus on. How have you seen these terms represented in the media? Which ones stood out from the word cloud?

Brisa Abapori (BA): Esas palabras coinciden porque bien sabemos que en Charagua hubo un incendio que afectó a los recursos naturales y [además porque] se incendió Ñembi Guasu, que es un área turística.

Brisa Abapori (BA): Those words are relevant because we know that in Charagua there was a fire that damaged natural resources and [also because] Ñembi Guasu, which is a tourist area, was also affected by fire.

RV: According to the word cloud, how have the terms you chose been represented in the media?

BA: En cuanto al incendio de Charagua, sí se ha visto en los medios de comunicación […] que se quemó bastante el bosque. Se necesitaba mucha ayuda y fue mucha pérdida de nuestros recursos, de nuestra flora y fauna.

BA: In case of the Charagua fire, the media […] showed that much of the forest burned. A lot of help was needed and it was a big loss of our resources, of our flora and fauna.

RV: What words should be represented for Charagua?

BA: A mí me gustaría que sobre Charagua se hable más sobre la cultura y al Gobierno Autónomo Indígena Originario Campesino (GAIOC), como bien sabemos Charagua ya hace cinco años que se convirtió en una GAIOC. Hoy en día se sigue diciendo que es un municipio. Me gustaría que se resalte más eso, […] por qué es importante el Gobierno Autónomo Indígena y en qué nos ayuda todo eso. En cuanto a cultura, me gustaría que se muestre la riqueza que tiene Charagua en cuanto a la cultura guaraní; que se muestre la danza, que se muestre las artesanías, la agricultura, la ganadería y otras riquezas […].

BA: When discussing Charagua, I would like the media to talk more about culture and the Autonomous Native Indigenous Peasant Government (GAIOC). As we well know, Charagua became a GAIOC five years ago, but currently it is still called a municipality. I would like the media to highlight it more, […] to talk about why the Autonomous Indigenous Government is important and how all this helps us. In terms of culture, I would like the media to show that Charagua is rich in Guaraní culture: the dance, the handicrafts, agriculture, livestock breeding and other forms of wealth […].

RV: During the workshop, the group created their own word cloud with terms that they consider representative. Explain what words you highlighted in your cloud and why?

BA: La palabra que destaqué fue «cruceño» […] porque me sorprendió que esté ese término en la nube de palabras sobre Charagua. Porque si bien sabemos que Charagua es un pueblo indígena, sí, tal vez hay lugares urbanos, pero en su mayoría es indígena, por eso me sorprendió mucho. Yo sé que estamos dentro de Santa Cruz, pero, creo que se debería dar a conocer más como indígena que como cruceño.

[…] La otra palabra que vi fue «municipio». Charagua ya no es un municipio, es una GAIOC, ya se debería de reconocer a nivel nacional como una GAIOC y ya no como un municipio.

BA: The word that I highlighted was “cruceño” […] [“from Santa Cruz”] because I was surprised that that term is in the word cloud about Charagua. We know that Charagua is mostly an Indigenous town, even if there are urban places, so that's why I was very surprised. I know that we are part of the Department of Santa Cruz, but I think we should be better known as an Indigenous territory than as a territory in the Santa Cruz Department.

[…] The other word I saw was “municipality”. Charagua is no longer a municipality, it is a GAIOC, it should be recognized at the national level as a GAIOC and no longer as a municipality.

RV: What topic is missing in the media in your area?

BA: Sobre mi zona nos falta que lleguen los medios para mostrar todo lo que sucede ahí. En general todo lo que pasa en mi zona, todo lo que es la organización, la cultura, falta muchísimo.

BA: We need the media to come in my region to show everything that is happening here.There is no discussion about the organization and culture in this region.

RV: What examples of harmful or incorrect information have you seen in the media or social networks about your area?

BA: Hay un medio que allá siempre publica, lo que no me gusta es que suben algunas noticias sin investigar más a fondo. Son algunas noticias que dicen: Tal persona hizo esto, pero sin embargo es otra persona la que está haciendo eso, no lo investigan a fondo.

BA: What I don't like is that the media publishes news without further investigation. For example, they publish news about the doings of a particular person, but nevertheless it is another person who did it. The media does not investigate it thoroughly.

RV: What do you want the people of the Gran Chaco to know about climate change in the region?

BA: Me gustaría que […] los medios lleguen a comunidades indígenas donde sí afecta demasiado y donde hay mucha escasez de agua y de alimentación. El agua se está secando y no han podido sembrar porque no hay lluvia […]. Los medios deberían resaltar [eso] para que pueda llegar alguna ayuda.

BA: I would like […] the media to talk about the Indigenous communities that are greatly affected by it, where there is a great scarcity of water and food. The water is drying up and people have not been able to plant because there is no rain […]. The media should highlight [that] so that people could receive some help.

RV: What do you want the people of Bolivia and the world to know about climate change in your area?

BA: De mi zona me gustaría que sepan que nosotros nos sustentamos con la agricultura y la ganadería. No pudimos sembrar [en este tiempo] porque no había lluvia y lo único que nosotros hacemos es sembrar. En cuanto a la ganadería [también] afecta demasiado, porque gracias a eso — a lo que nosotros sembramos — igual se alimentan los animales. Que sepan que necesitamos ayuda, que hay muchas necesidades y [que] lleguen algunas instituciones para que puedan poner su granito de arena a cada comunidad indígena.

BA: I would like people to know that we support ourselves with agriculture and livestock. We couldn't plant [during this time] because there was no rain and the only thing we do is plant. The livestock was [also] affected very much, because what we sow we also feed to the livestock. People should know that we need help, that there are many needs and [that] some institutions could contribute in helping each Indigenous community.

Categories

Support our work

Since Rising Voices launched in 2007, we’ve supported nearly 100 underrepresented communities through training, mentoring, microgrants and connections with peer networks. Our support has helped these groups develop bottom-up approaches to using technology and the internet to meet their needs and enhance their lives.

Please consider making a donation to help us continue this work.