A version of this article will soon be available in Tlahuitoltepec Mixe.

By María Alvarez Malvido in conversation with Tajëëw Díaz Robles

The language at a glance

“Tlahuitoltepec Mixe is a Mixe language spoken in Mexico. It consists of a core dialect, spoken in the towns of Tlahuitoltepec, San Pedro y San Pablo Ayutla, and Tamazulapan, with divergent dialects in Tepuxtepec, Tepantlali, and Mixistlán. It is a polysynthetic language with head marking and an inverse system.” – Wikipedia [2]

Recognition: One of the 68 Indigenous Languages recognized as “National Languages”

Digital security resources in this language:

- None identified

Digital security tools in this language:

- Signal ❌

- TOR ❌

- Psiphon ❌

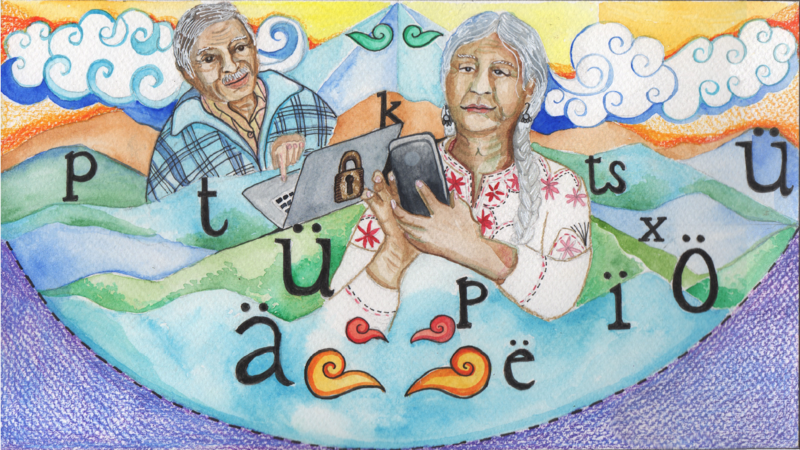

In the Mixe mountains of Oaxaca, Mexico, there are two closely linked initiatives originating in the territory: the revitalization of the Ayuujk language and the creation of its own training spaces. Among these processes created based on autonomy and community organization, the recent development in the use of digital technologies raises questions and proposals on how to safely use them. What do people who speak Ayuujk think about digital security? What perspective do those who have also been engaged in their language literacy for so many years have?

Questions like these go beyond the digital security view commonly held by young people, to involve the experience of the elders, and listen to them. They arise together with proposals from the diverse experiences of living in the territory and being bilingual, specifically that of the community of Santa María Tlahuitoltepec. Some of these experiences, such as those of the activist Tajëëw Díaz Robles, become starting points to learn from retired bilingual teachers, acknowledge their trajectories, their relationship with the mother tongue and their ability to look back to the past in order to confidently continue towards the future.

“Tlahui,” as the community is commonly known, is located in the upper part of the Sierra Mixe where a large part of the Ayuujk (or Mixe, in Spanish) people live; they are known as “the never-defeated” for their historical resistance to various colonization processes. Currently, out of 19 Mixe municipalities, 17 are governed by Indigenous regulatory systems, which are established within the communities and do not have direct or regulated interference from political parties.

Various people, projects and communities around the world have learnt from Tlahuitoltepec community organization, its defense of autonomy and diversity from the local level. A deep and complex network, and to a certain extent impossible to understand in its entirety for those who approach it as akäts (as people from outside the Mixe territory are called in Ayuujk). However, there are projects that clearly reflect those long community processes that, although they exist from and for the territory, teach important lessons to the world.

To mention a few examples, there is the renowned Center for Musical Training and Development of the Mixe Culture [3] (CECAM) where musicians from all over the region have been trained for more than thirty years, with training methodologies that respond to the indispensable presence of the philharmonic bands in the region. Also, the community training project at a higher level, as the Intercultural Communal University of Cempoaltépetl [4]-Communal Autonomous University of Oaxaca (UNICEM-UACO) offering degrees designed from and for the community, such as those in Communal Communication and Territory, that of Bien Vivir Communal (Community Good Living) and the next master’s degree in Ku'ayuujk Mixe Communal Linguistics.

On the other hand, there are the statements [5] and decisions of the community regarding the plagiarism of its traditional blouse by foreign and exploitative companies. Since 2015 this has created an important precedent to discuss multicultural racism in the purchase and sale of native textiles in Mexico [6] and create protection mechanisms for them. Also, the more than 20 years of experience in community communication through the Jënpoj community radio, and whose development has also been an important precedent in the recognition of Indigenous media in Mexico.

Although linguistic activism is interwoven with the previous examples, there are also several specific examples from Tlahui and the Mixe region that show a community and inter-community organization for the strengthening of the Ayuujk language (or Mixe, as it is called in Spanish). One example is the Weeks of Mixe Life and Language (Sevilem), which for more than thirty years have been a space to support the study of the Ayuujk language and culture, articulating the experience of different community actors such as elders, bilingual teachers and young people from diverse communities.

In a more recent space that continues the linguistic revitalization in the Ayuujk region, the Colmix [7] is also an example of articulated efforts that recognize the need to continue reflection and defense of the language, and honor its resistance to so many years of colonization. Also, to question the strategies and research carried out from abroad in order to build their own investigations and problematize the narrative that has been built around Indigenous languages. And finally, as a space to explore the questions that arise from using the language on various platforms or formats, such as digital spaces.

Tajëëw, originally from Tlahui and a member of the collective, shares some reflections on creating digital security strategies in her community. These ideas are the result of a research in her community in collaboration with Rising Voices, which consisted mainly of investigating the establishment of telecommunications in Tlahui, and listening to three retired teachers from two communities: one is Tlahuitoltepec and the other San Pedro and San Pablo Ayutla. Both belong to the upper area of the region, with two “comunalects” (speaking communities which have a high level of intelligibility) and whose territories are half an hour from each other by public transport.

Listening to retired teachers when thinking about digital security in relation to language is relevant in order to create concrete strategies, learning from their life stories, and their central role in the development of Ayuujk literacy. To understand why this is significant, it is necessary to look at their specific experiences in a community like Tlahui.

Ayuujk, teachers and language activism

For Tajëëw, teachers have played a fundamental role as mediators between Indigenous peoples and the Mexican state, especially in the second part of the last century in the case of the Mixe region. At first, they acted as avenues or mechanisms for the imposition of Spanish language and the inclusion of peoples in the national project in Mexico. Some also had personal and collective initiatives for the development of community education, whose focus is the revaluation of the Ayuujk language. Tajëëw explains:

“There was a permanent demand for schools and communication technologies in the region, first the roads and later the computers, telephony and the internet. It is in this context that the role of the teachers, most of them currently retired, becomes relevant and important. They are not familiar with technology, however, due to their work they saw the need to use various technologies, despite their distrust due to their lack of knowledge and currently distrust due to all the threats these technologies pose.”

Listening to their experiences should focus on recognizing their feelings related to digital technologies; acknowledging their role in efforts to promote the use of the Ayuujk language, and their own experience of learning the language. In other words, it is not only about speakers but also about people who participated in a bilingual educational system and have had a training process — formal or informal — in which they have thought about and developed grammar and literacy bases. This is important when we consider that the use of the Mixe language on social media, webpages and emails depends to a large extent on the mastery of its writing.

To understand this relevance, which is not focused solely on the orality of the language, Tajëëw explains the need to recognize another key argument. It is about rethinking the discourse that the original languages are only oral and do not have writing. Tajëëw, and the collective work from the Colmix, questioned this narrative, and discussed the importance of recognizing that several living languages, such as Ayuujk, were interrupted in their own path to developing writing, by colonization. In other words, “limiting them to orality becomes a narrative that contributes to their discrimination and limits their development in written support.”

Failing to recognize the writing possibility of the Indigenous languages is also reflected in the digital world; for example, in the absence of localized digital platforms in various languages, which could lead to a more local management of digital security issues. Why then not listen to the pioneers in the activism of one of the languages that endures in the world? Those whose life stories are part of the development of Ayuujk writing?

Need for information and training on digital security

This context reaffirms the need to know more about the views on digital security of the elderly. Some of these views identified by Tajëëw in conversation with three retired teachers are related to practices that they carry out around the secure use of passwords and information backups. However, they all shared doubts that generate distrust in the use of digital technologies. For example, the uncertainty around the location registration for smartphones, without knowing why or how they could change that configuration. Or experiences of scams via Facebook or WhatsApp from people who request bank transfers through the identity theft of other users. In this way, it is just as necessary to consider their views and address their doubts about digital security, as it is to learn from their experiences in relation to language. This will support them with information on habits and strategies that ensure security for their communication and linguistic revitalization in the digital world.

To achieve this, explains Tajëëw, it is necessary “to recognize the ability of older adults to use technologies to transmit their languages, not only in their families, but also to a broader public.” From this first approach, four specific recommendations emerge to meet the needs of safely access to information on the internet:

- Designing and organizing workshops for older people on security issues with topics such as the use of passwords and phone encryption, as well as ways to use social media more safely. It is essential taking into consideration the importance of spaces specially designed for age groups to choose what type of information and how it is shared.

- Designing and implementing training to organize and back up information from telephones and computers, both for their daily communication and for the safe storage of testimonies and documents of the elderly. Similar to the previous one, recognizing the potential they have in the use of technologies with greater confidence and security.

- Ensuring that the workshops be in Ayuujk language and that information continues to be broadcast on the local community radio. The development of audio content, especially for community radio stations, and lately a combination of the use of the podcast format and then its broadcast on radio, allows us to envision this as a useful medium for disseminating information on digital security.

- The information must come from established spaces that have experience with the specific subject, whether from non-governmental organizations, groups and training spaces, considering that there is mistrust about the type of information that is shared.

Although these reflections arise from the specific context of the upper Mixe region, they are one more example from which to learn and broaden our perspective when we think of “digital security” in relation to Indigenous languages such as Ayuujk. These regard other native language contexts, as well as conventional approaches in which strategies and collaborations towards digital security are discussed. Listening and recognizing elderly people’s life experiences as bilinguals and pioneers of language activism could lay the groundwork for local strategies that offer greater security to those who make the world a more diverse space.

For more stories and information from participating language communities, please visit the “Digital Security + Language” [8] project page