Yamil Lora from The Point CDC in the South Bronx performs site surveys for a new resilient wireless network. Photo: Danny Peralta.

Rising Voices (RV) is partnering with the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) which produced the 2018 Global Information Society Watch (GISWatch) focusing on community networks defined as “communication networks built, owned, operated, and used by citizens in a participatory and open manner.” Over the next several months, RV will be republishing versions of the country reports highlighting diverse community networks from around the world.

This country report was written by Greta Byrum and Diana Nucera of The New School's Digital Equity Laboratory and the Detroit Community Technology Project. Please visit the GISWatch website for the full report which is also available under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Our story begins almost a decade ago, when new technologies enabled resistance and sparked a wave of digital activism in Tunis, in Tahrir Square, in New York City's Zuccotti Park and Washington DC’s K Street, and around the world. Many groups in the United States (US) recognized the potential of that moment: long-time advocates for media justice and literacy, public access media organizers, builders of community Wi-Fi and low-power FM radio, community organizers and civil rights leaders, open tech and data advocates, hackers and policy strategists. This is the story of a vision that emerged among people working together to create community resilience and digital justice between Detroit, New York City, Washington DC, and eventually in collaboration with international partners, by building community-owned internet infrastructure.

Community technology and digital stewardship

Wireless internet can unlock the enormous potential in our local communities. These opportunities can only be sustained, however, if networked technology projects are led by people who are deeply invested in their community’s welfare; that is, people with a deep understanding of – and a desire to maintain – the fabric that binds their community together. – Diana Nucera

Community networks in the US have long struggled to grow in parallel with the large international community networks that emerged, particularly in Europe. Some US standouts have achieved a sustainable operating scale and model, and have provided a critical long-time service for their communities. Tribal Digital Village Network (TDVNet) has been bringing free internet to community anchors in indigenous territories since 2001, currently with over 350 miles (over 560 kilometers) of point-to-point and point-to-multipoint links supporting 86 tribal buildings (and providing a net neutral service). Monkeybrains in San Francisco is a nimble independent local wireless internet service provider (WISP) which uses a combined millimeter-wave, mesh and point-to-point system to serve 5,000 locations on a sliding-scale basis. Sudo Mesh is a five-year-old community-owned and run local mesh network serving Oakland, California, while Meta Mesh in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania has built out to 65 live sites comprised of 109 devices. And NYC Mesh has built out 178 nodes using volunteer labour and a decentralized governance model.

An access point tower constructed by Tribal Digital Village overlooks Pala, California. Photo: Tribal Digital Village.

But unlike guifi.net, Freifunk or Rhizomatica, in the US we do not have a long history of expanding networks beyond discrete geographic areas or particular use cases. This has a lot to do with the consolidation and the political power of the incumbent telecommunications industry, which has taken many steps to place a stranglehold on local broadband by creating state-level prohibitions on ownership of broadband facilities by city governments and by starving local networks of backhaul (bandwidth) by buying out or blocking competing wholesale bandwidth providers. The capture of the US Federal Communications Commission at the national level by industry lobbyists has also had a global effect by catalyzing the recent repeal of net neutrality (the Open Internet Order of 2015).

Another issue that has challenged scale for community networks in the US is that many do not find a subscriber base beyond loyal techie advocates and small communities. Without a broad base of users – including those who may not be able to afford the high cost of monopolistic broadband service, or who may not have (or want to have) the skills, time or patience for troubleshooting a do-it-yourself (DIY) system – community networks often rely upon one or two staff, or just volunteers. So, ironically, some community networks with a flat or decentralized governance approach end up serving already information- and technology-rich areas, since those areas are where volunteers live and work.

As journalist and community network documentarian Armin Medosch puts it, “far-sighted techies tend towards a linear extrapolation of technologies into the future without considering other factors, such as politics, the economy, the fundamental differences between people in class based societies.” Similarly, Alison Powell’s research on community networks points out their tendency to reinforce “geek publics” rather than the “community publics” they purport to serve. In the complex political and economic context of the urban US, the political and economic challenges around digital infrastructure, access and inclusion have kept many US community wireless networks from achieving or sustaining scale.

Commotion Wireless

Starting in around 2008, a group of media justice and community wireless activists had a different vision for community wireless. Led by developers and media activists who had built Champaign-Urbana, Illinois’s Indymedia Center and its CUWiN network, the Open Technology Institute (OTI) began developing Commotion, envisioned as an integrated plug-and-play OpenWrt-based mesh networking platform that communities could easily deploy, and which included secure encryption and a suite of locally hosted applications. With device-based peer-to-peer dynamic mesh routing, Commotion would be able to work with or without a connection to the global internet, and to route traffic around points of failure automatically. Based on the principles of security, resilience, and local control, Commotion would be an open-source local communication and media platform to be used from Tahrir Square to Detroit, in emergencies from Mubarak to Katrina.

In 2011, OTI started testing beta versions of Commotion in the field in multiple locations, often working with groups who were familiar with local media and DIY radio “barnraisings” and interested in trying new technologies to advance their work – for example, the Media Mobilizing Project in Philadelphia, the Allied Media Projects in Detroit, and Occupy K Street in Washington DC. Like many other attempts at building local wireless, these early tests showed that without enough local techies and engineers with dedicated time to spend fixing things, networks would break frequently, users would get frustrated, and user confidence and numbers would decline. Furthermore, stable electricity and bandwidth were a challenge in some locations, and depended on local relationships and governance – that is, network representatives to be in charge of different aspects of the networks, from physical hardware to communicating with users and node hosts.

The Detroit Digital Justice Coalition

Meanwhile, in the summer of 2009 at the Allied Media Conference in Detroit, a group of leaders came together to investigate the role that local technology projects might play in restoring communities harmed by the US economic crisis, by training people how to use the internet and technology to create local micro-economies. The resulting Detroit Digital Justice Coalition (DDJC) was comprised of 13 member organizations and individuals including seniors, youth, environmental justice communities, welfare rights activists, hip hop community organizers, community gardeners, independent technologists and designers, each one believing that communication is a fundamental human right. The DDJC had a plan to bring whole communities online, not just isolated individuals, so the internet would be a welcoming environment for new users.

For decades, Detroit has topped the list of “worst-connected cities” nationally, with 2013 data showing nearly 60% of its residents lacking in-home broadband subscriptions and 40% lacking any connection whatsoever; 38% of Detroit residents live below the federal poverty level, and since 2014, tens of thousands have faced water shut-offs and evictions due to tax foreclosure. Yet offline, Detroit’s organizers knew that vibrant community leaders have been steadily transforming the city from the ground up with community gardens, land trusts, co-ops and a thousand other grassroots initiatives enabling local self-determination. As Allied Media Projects describes in their Media Literacy Guide, the DDJC’s goal was:

[T]o use digital technologies to strengthen these efforts, interconnect them, and make them more visible. This would shift the online narrative of the city while propelling communities to rewrite their offline reality – growing businesses, community programs, and community infrastructure through media-based organizing skills.

The Coalition first started building their vision for digital justice offline by collaborating on a set of shared principles. To develop a common understanding of how to shape the role media and technology might play in communities, the Coalition asked members to answer the following questions:

- How are you currently using media and technology for organization and economic development?

- What kind of support and collaboration would make your work stronger?

- What should digital justice in Detroit look like?

The Detroit Digital Justice Principles were born through this process, presenting a unifying definition of what digital justice means to the community: access, participation, common ownership, and healthy communities, each one describing a different aspect of digital justice.

With these principles and a proposal focused on a “community technology” approach to creating healthy technology ecosystems, the DDJC’s member organizations got to work implementing their vision through the BTOP federal broadband stimulus program. The Detroit Future programs built networks of teachers, youth and artists and trained them in to use media production and web development for organizing, teaching and helping small businesses. By 2011, the Detroit Future programs had trained hundreds of Detroiters of all ages to use technology on their own terms to address a range of issues from housing to environmental degradation to water shortages, while also providing a platform for the city’s growing creative entrepreneurship.

At the same time, OTI was working hard to solve the problem of how to maintain and expand Commotion community wireless networks locally, including in Detroit. In order to provide local technologists, builders and organizers with documentation, tools and resources, OTI together with Detroit-based social enterprise The Work Department developed a prototype “Neighborhood Construction Kit”, which included information modules on everything from how to make a flyer to promote your network to how to install a chimney mount on a rooftop. With additional technical information on how to configure Commotion firmware on standard routers (mostly Ubiquiti) and other devices like Android phones, this became the Commotion Construction Kit and moved online to live as documentation on the Commotion Wireless GitHub site.

Still, even with resources available online, OTI found it difficult to build a stable foundation of network support among local organizations and advocates, especially when local organizations had so many competing demands on their time personally and in their community leadership work. It would take more organizing, tapping into local movement building, dedicated expertise and resources, plus a whole new approach to building a new tech-supported economy and a method for teaching different kinds of learners about how to build and maintain networks. Detroit’s organizers and community technologists once again held the key to bringing these efforts together.

The Detroit Community Technology Project

By training local residents to be “digital stewards” of the networks, community organizers create employment opportunities and provide public Internet access while strengthening social networks within the community… At their most ambitious, these projects suggest a different way of thinking about work in the digital future: that we might manage our digital ecosystem with care and intention rather than constantly disrupt and respond to disruption. At minimum, these projects show the importance of localism and workforce development to maximize the economic benefits of new networks and produce technology that is attuned to a community’s needs. – Joshua Breitbart

In 2012, the DDJC and the Allied Media Projects’ Detroit Future Media partnered with OTI to create the Digital Stewards Program, which trains neighborhood leaders in designing and deploying community wireless networks with a commitment to the Detroit Digital Justice Principles.

The Digital Stewardship training program is based on the pedagogy of popular education, including the idea that everyone brings valuable knowledge and experiences into any learning space. Instructors take the role of facilitator, building peer-to-peer educational conditions through activities that work for all types of learners. This approach includes a process of envisioning all of the ways we can use a community network to strengthen neighborhoods and solve local problems, beyond simply gaining access to the global internet. The Digital Stewards Program led to the formation of the Detroit Community Technology Project (DCTP) in 2014. DCTP was developed to encompass broader community technology education, to organize work and to share best practices.

In 2014, OTI and DCTP received funding to work internationally to implement an international Community Technology Seed Grants program, supporting 11 community groups internationally to adopt and modify the training for their own contexts. In the process of implementation, OTI and DCTP found that many international groups would have difficulty obtaining hardware that would reliably run Commotion, or that they were trying to achieve different community goals from what the platform would support. So the project forked again, this time moving all of the organizing and general wireless curriculum onto the Community Technology Field Guide so that it could be more generally applicable for different kinds of community technology projects, including but not limited to Commotion.

International Community Technology Seed Grantees. Photo: Detroit Community Technology Project

Red Hook, Brooklyn and Hurricane Sandy

In 2012, shortly after Digital Stewards launched in Detroit, OTI also helped bring the Detroit Digital Stewardship curriculum to Red Hook Initiative (RHI) in New York. RHI wanted a mesh network to create a local online youth-produced radio station, so with OTI’s help they adapted the Digital Stewardship curriculum on basic community organizing, wireless engineering and construction for their workforce training program for young adults living in public housing, and added learning modules on video production, web design, and professional development. In partnership with Parsons student Alyx Baldwin, RHI held participatory design workshops with residents, and by the fall of 2012, RHI’s Digital Stewards had built a small network serving some of the major public spaces and community anchors in the neighborhood.

Although New York is a wealthier city than Detroit, many of its residents face similar challenges in accessing broadband service: 31% of New Yorkers currently do not have broadband service at home, including 32% of Black and 33% of Latinx New Yorkers. That is considerably more than the 21% and 23% for White and Asian residents. Geographically, service is also not equitably distributed. In some neighborhoods, people would have to pay on average 5% of their income on cable service in the current market, and would have only one option for service.

When Hurricane Sandy struck New York in October 2012, flood-prone Red Hook was devastated. Cell phone service was down and internet service went out in places. The neighborhood was dark, with chest-deep water in the streets – but with its small mesh network, RHI was still able to connect to its staff and communities in parts of the neighborhood that had no communications or power at all for weeks after the storm. RHI organized volunteers using the mesh to help distribute supplies to elders and others unable to leave the public housing towers in the neighborhood, and gave the community a voice online to broadcast what was happening. People all over the world following RHI’s Twitter feed put together online shopping lists and shipped supplies to Red Hook.

Though the Red Hook WiFi project was in the works before Hurricane Sandy struck, it gained prominence and media attention after the storm. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) boosted RHI’s broadband connection with a satellite uplink, so where the regular internet was unavailable, residents and government workers could log on to the mesh to quickly find out where to pick up supplies or find government officials. Neighborhood building owners who had been wary about allowing RHI to install equipment on their rooftops joined the network, seeing its importance in areas of the community where power and communications were out. The City of New York opened up a funding opportunity for projects like Red Hook WiFi, which had provided critical community-led service in the aftermath of the disaster using innovative technology.

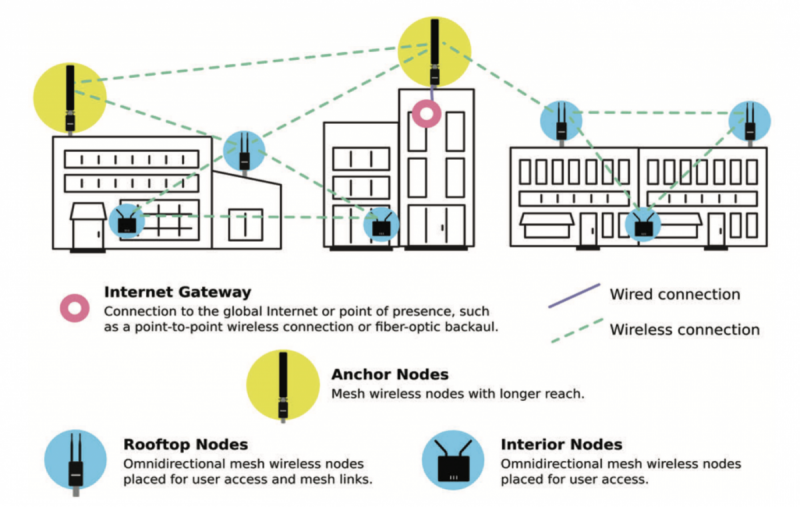

Community technology network distribution diagramme.

While RHI had led the Red Hook project, OTI had provided the link to the Detroit curriculum and helped to adapt and implement it. Building upon the success in Red Hook, OTI’s umbrella organization, New America, was awarded a contract with the City of New York’s Economic Development Corporation (EDC) using a federal Sandy recovery grant to scale up the Digital Stewardship approach in New York City, and created its new Resilient Communities (RC) initiative. Resilient Communities started work in 2015 by seeding funding and resources among community leaders and community-based anchor organizations committed to building resilience and supporting affected communities in five low-income Sandy-impacted neighborhoods throughout the city (East Harlem, South Bronx, Far Rockaway, Sheepshead Bay and Gowanus). At the same time, the Red Hook Initiative also won a Sandy recovery contract from the City of New York’s EDC to expand its network and add solar panels to increase resiliency. The City meanwhile embarked on an effort to build out free wireless systems in the Red Hook public housing development and two other New York public housing sites, Queensbridge and Mott Haven Houses, looking to weave together integrated systems of community- and City-led Wi-Fi throughout the city.

2018: Community technology in Detroit and New York

To meet the need of scaling up the Digital Stewards program for the five new communities, New America’s Resilient Communities team once again teamed up with DCTP to expand upon the Digital Stewards training programs, adding emergency management plans to the Digital Stewardship trainings based on an understanding of building resilience as a process of building trust and relationships, not just technological systems.

Detroit Digital Stewards install networking equipment. Photos: EII

In the meantime, while the NYC Resilient Networks project launched in 2016, the Detroit Community Technology Project was also launching its new Equitable Internet Initiative (EII), a program training local residents on wireless broadband internet sharing in Detroit neighborhoods, expanding the number of networks in the city built by Digital Stewards from around eight to 11. As we launched our work at both sites, Resilient Networks commissioned DCTP to develop the Community Technology Handbook, a resource to share the approach and pedagogy of popular education for community technology to train Digital Stewardship trainers in both cities. Following the model of the Detroit Digital Justice Principles, project leaders also started the work by developing a set of shared principles to guide and ground the work in community needs.

The Detroit Community Technology Project’s Teaching Community Technology Handbook.

Resilient Networks NYC is designed to withstand shocks and stresses and provide community-maintained and cooperatively owned critical telecommunications infrastructure in flood-prone areas of New York City. But in the summer of 2017, even as Resilient Communities and partners had trained some 30 Digital Stewards citywide, and hurricanes were about to hit Houston, Miami and Puerto Rico, the Resilient Communities Project had not been able to build a single node yet due to bureaucratic constraints (federal disaster recovery funding controlled by the city but regulated by federal officials has created multiple bureaucratic hurdles due to permitting, paperwork, environmental review, etc).

Racing to develop a plan for that hurricane season, Resilient Communities adapted its planned network repair kits to develop the Portable Network Kit (PNK). The PNK is a collection of off-the-shelf consumer hardware that can be configured easily to make your own local online or offline Wi-Fi network for about USD 800 to USD 3,000, depending on the battery system. The PNK connects devices in a small area – anywhere from one building or public square to about a half square mile (1.3 square kilometers) if you add or “mesh” additional Wi-Fi devices to create a wider range. If you add additional kits, you can mesh them together to create an even wider range.

PNKs have found their way to Dominica and Puerto Rico post Hurricane Maria, and EII is now beginning to incorporate them into its network as well. Every participating partner in New York City will have PNKs to build out and expand their networks in emergencies or for community events and programs.

Scaling up the community technology approach to resilience

Revolutionary solidarity is what love looks like at scale. – Diana Nucera

As developed through the partnerships in Detroit and New York, community technology is a method of teaching and learning about technology with the goal of restoring relationships and healing neighborhoods. Community technologists are those who have the desire to build, design and facilitate a healthy integration of technology into people’s lives and communities, allowing them the fundamental human right to communicate.

We believe that increasing resilience means building and deepening relationships and developing creative solutions to strengthen communities in times of change and uncertainty. Our work starts from a set of core principles that focus on listening, participation and equity as a foundation for building community resilience. We work with local leaders and groups to uplift and share creative, visionary and locally rooted solutions – and to make the systems and institutions they depend on more responsive.

With the current global emergency due to climate change, a rising tide of authoritarianism, and the nearly unchecked power of big tech, we see a critical opportunity now to develop future-ready solutions together with the communities most affected by these crises, particularly through the redesign and rebuilding of brittle physical and digital infrastructures.

Next up for DCTP/EII and Resilient Communities: DCTP will publish the Community Technology Workbook, which contains six years of learning modules and programming primarily designed by DCTP through the work and partnerships in Detroit and New York. Meanwhile, network build-out continues, as does the process of developing sustainable business models for all network anchor organizations in Detroit and New York City.

Our collaboration responds to all the tectonic political events and intertwined social, economic and natural disasters of the last decade: we in the US have learned about resilience from Maria, Katrina, Sandy, the Flint and Detroit water crises, PROMESA in Puerto Rico and emergency management and the foreclosure crisis in Detroit, the US nation’s ongoing oppression of people of color and immigrants – and of course the rise of Donald Trump, the spread of surveillance, algorithmic and predictive criminalization, and tech-enabled targeted deportation. We recognize that crises like these are happening around the world. Our hope is that, in the same way we have been able to scale our work in the US by creating an adaptable model of teaching, learning, and responding to local needs and circumstances, others around the world can adapt and scale up the community technology approach and tools.

For more information regarding action steps for the United States, please visit the full report on the GISWatch website.