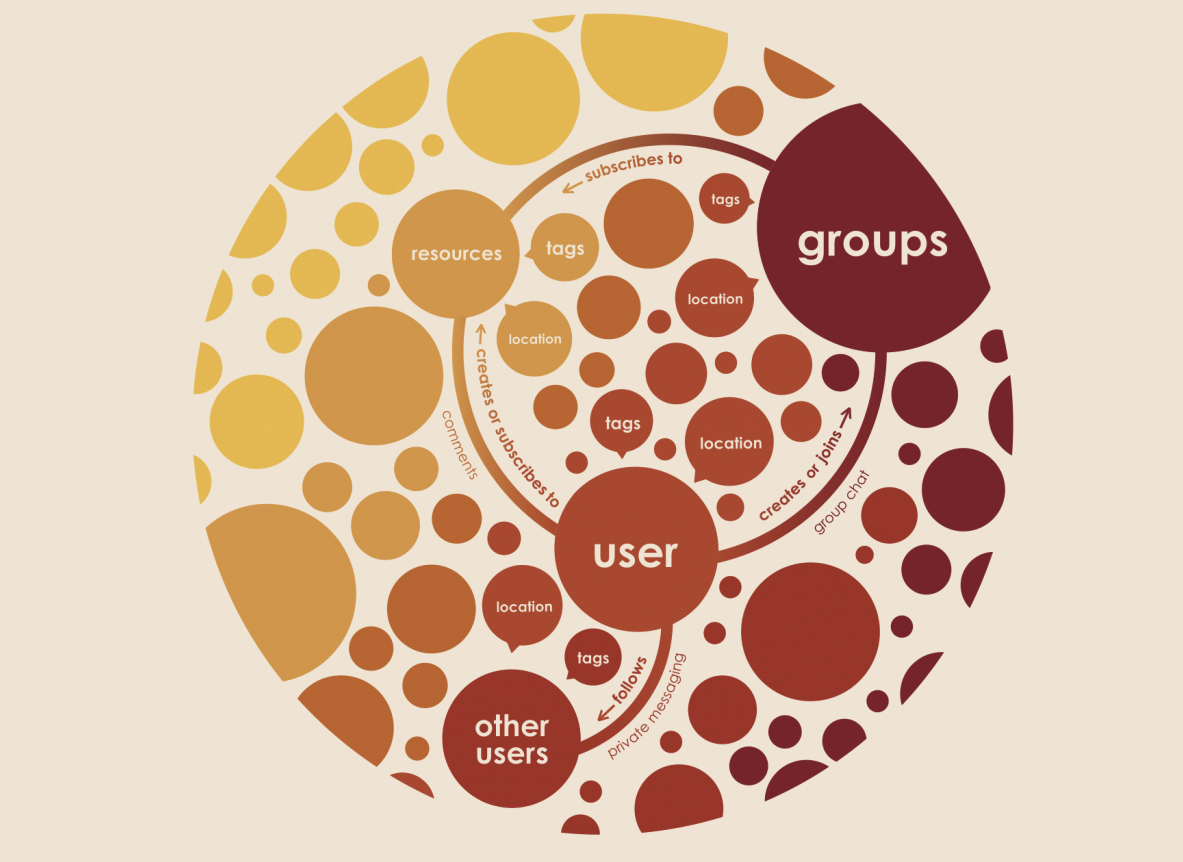

From an infographic from mycitizen.net

This guest post was written by Christoph Amthor, the co-founder of the non-profit NGO Burma Center Prague and creator of the project mycitizen.net. This post was originally published as a longer series of three on the Ethnos Project.

Mycitizen.net is a free and open-source platform that facilitates social networking in local communities. It has been designed from the outset for the specific needs of civil society, particularly in closed societies and countries in transition. It can be used with mostly unsupported languages, where the Internet is very slow, and where the safety of civil society actors requires special privacy protection.

After the general elections in November 2010, Myanmar (also known as Burma) underwent considerable changes – some of which have deeply affected everyday life. Our organization, the Burma Center Prague, is based in the Czech Republic, a country still catching up with Western Europe. Due to our own experience, we naturally emphasize the importance of civil society for a successful transition towards a genuine democracy, and the need to cautiously tailor all efforts in Myanmar to the local setting.

Ethnicity and religion are defining opportunities and exclusion during today's reforms. Myanmar boasts a wealth of roughly 130 officially recognized ethnicities – not including the Rohingyas, who are systematically being disenfranchised. The current reforms in Myanmar follow a top-down approach, and it is doubtful whether all parts of the population will benefit and be actively involved. Obstacles such as unequal access to school education and discrimination against ethnic minorities are deeply entrenched. Fortunately, civil society on the ground is engaged and local charitable activities have a firm place in daily life.

In addition, Myanmar is going through what we might call a “handheld revolution.” The country was once infamous for its poor power grid, very low technology penetration, and heavy censorship with draconic repercussions. Myanmar was also one of the countries that “pulled the plug” to prevent the free flow of information during the “Saffron Revolution”. Only a few months after the opening of the country, even remote towns are now lined with stores selling smartphones. The omnipresence of handheld high-tech is in stark contrast to the extreme prevalence of low-tech in nearly all other aspects of daily life.

It seemed obvious that we should try to remedy the lack of citizen involvement at the grassroots level by using the growing opportunities presented by technology.

When we began, in 2011, political reforms had been promised but not yet started, and the “handheld revolution” was a mere projection. However, we could not afford to wait for perfect conditions, with an estimated three-year timeline for the project. It felt like launching an aircraft to a place where the airport was still under construction.

We decided that we would try not to compete with existing solutions but to create a niche product in response to very specific needs.

A video on how it all works:

The concept for mycitizen.net began from a simple structure of three basic elements: users, groups, and resources.

Users form groups of common interests and concerns, groups then are the main focal points of activity and communication. In order to spark activities that go beyond chatting, users and groups need to have resources available, such as documents, videos, audio recordings, events, or links to anything on the web or in the real world.

Everything can be enriched by metadata, including tags, mapped locations, and multi-lingual descriptions. Metadata can help users identify items. A user can, for instance, search for hospitals providing HIV treatment around her hometown, or globally for groups of people who have the same concern.

Therefore, we understand “relevance” differently than on many social media platforms where information value decreases over time, and popular items push others out of sight. We understand relevance as a very personal assessment, which you should be able to control at any time. Users also need to remain in control of their privacy, especially as many civil society activities require special protection, leading to multiple levels of security and visibility for users.

Obviously, the platform needed to be accessible through a mobile device – one advantage of this is that apps need a much smaller data flow to use a service, making them today’s preferred tools to use the Internet in Myanmar.

Since the technical requirements are low, any group can run their own deployment on an ordinary PC and connect with their laptops and smartphones via Wi-Fi. For those groups that find it difficult to install and maintain the software on their own servers, we plan to offer a hosted turnkey solution.

Development is ongoing. We are now in beta testing with the public, and dissemination will largely depend on training. Although mycitizen.net was designed for Myanmar, we are interested to explore potential applications in other regions and for other communities.

If the story of mycitizen.net has made you curious, I invite you to dive into the latest version using our demo deployment and to check out the general project website.

All images created by and republished with permission from mycitizen.net.

Support our work

Since Rising Voices launched in 2007, we’ve supported nearly 100 underrepresented communities through training, mentoring, microgrants and connections with peer networks. Our support has helped these groups develop bottom-up approaches to using technology and the internet to meet their needs and enhance their lives.

Please consider making a donation to help us continue this work.

1 comment