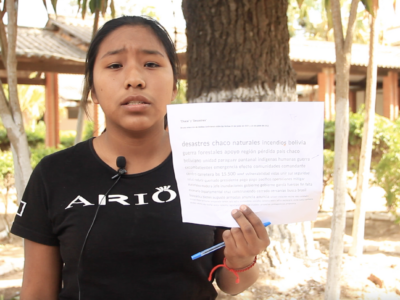

Image by Noran Morsi for Global Voices.

This article is written by Saman Daoud. It is part of a series examining free expression and information access in civic spaces across six language communities in the MENA region.

In the vibrant landscape of the Middle East challenges, addressing Assyrians’ freedom of expression necessitates examining the ongoing political marginalization they endure in their Indigenous homeland that spans contemporary Iraq, and some areas in Turkey and Syria. Their story is a reflection of the struggles faced by minority communities in a region marked by political turbulence.

As the world marked the Assyrian New Year, reaching the remarkable year 6773, celebrations echoed across Iraq, Syria and beyond. However, beneath the surface, a profound sadness gripped Assyrian minorities who stayed in their ancestral homelands, from Duhok, and Erbil to Nineveh, and Baghdad in Iraq.

Over the past two decades, ongoing oppression, ethnic and sectarian conflicts and political unrest have sharply reduced the Assyrian community in the Middle East. Many have fled to Europe, the US, and Australia, endangering the Assyrian language, with its 3000-year history in its native Middle Eastern home. The Assyrian population in Iraq has declined significantly, plummeting from an estimated 800,000 to 1.4 million in the 1990s to less than 142,000 today, as reported by the Shalma Foundation, an organization dedicated to documenting the populations of the Assyrian Chaldean Syriac people in Iraq.

This decline can be attributed to the region’s shifting political landscape, particularly in the aftermath of the US invasion of Iraq, which has cast a long shadow over the Iraqi people to this day. Successive Iraqi governments have failed to protect Assyrian communities from terrorist groups like the Islamic State (ISIS) and the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). The latter has aggressively sought control over Assyrian ancestral lands in Nineveh, even using Assyrians as human shields during confrontations along the Iraqi–Turkish borders. This coercive tactic aims to intimidate Assyrians into leaving.

These challenges have reshaped the Assyrians’ way of life, affecting their human rights and, notably, their freedom to express their identity, culture, and language.

As per Assyrian Policy Institute, Assyrians in Iraq declined by nearly 90% after the Iraq war.

That's how delicate demographics are. Things can turn turtle when a regime changes. pic.twitter.com/Nvslh5wDSW— Pradip Varma (@Pradip_K_Varma) June 26, 2023

The struggle of the Assyrians to express their identity over the last century

In the Middle East’s diversity, the Assyrians emerge as a distinctive Indigenous minority with unique ethnic, religious, and linguistic identities. They trace their ancestry back to the ancient Assyrian civilization that flourished in Mesopotamia, now Iraq. While predominantly Christian, the Assyrians also include smaller Muslim and Yazidi minorities who identify with their Assyrian heritage.

Assyrian Empire pic.twitter.com/O7ZpN1DJO3

— Sumerian and Hittite Language (Hasan Türk) (@SumerianHittite) July 27, 2023

The Assyrians have endured marginalization since the collapse of their empire in 609 BC.

In the dawn of the 20th century, along with other regional ethnic groups, Assyrians suffered under Ottoman rule, marked by Turkification policies that aimed at imposing a singular identity. This era witnessed Ottoman genocides against Assyrians, Armenians, Yazidis, and others, forcing Assyrians to flee and hide their cultural, religious, and linguistic identity out of fear for their lives.

Hakkari Assyrian Homeland – Let Them Not Return

Haydar Bey, the governor of Mosul, was given in May 1915 the power to invade Hakkari. Talaat Pascha,interior minister of Turkey, ordered him to drive the Assyrians out and added, “We should not let them return to their homelands”. pic.twitter.com/yQR56p60J4

— Athro ܐܬܪܐ (@athro14) July 26, 2023

Following World War I and the fall of the Ottoman Empire, Assyrian oppression continued as the Kingdom of Iraq emerged under British mandate. Assyrians had sought an independent entity in exchange for their army service, but Britain's failure to uphold its promises led to hostility and oppression by the newly formed Iraqi government.

In 1933, the Iraqi army brutally targeted over 60 Assyrian villages in the infamous Simele massacre, claiming over 3,000 lives. This massacre posed a real threat to the Assyrian presence in the region, prompting another mass exodus.

In an interview with Global Voices, Saad Salloum, an academic specializing in Iraqi minorities, and an Assistant Professor in International Relations at Mustansiriyah University in Baghdad, highlighted that the Simele massacre deepened the distrust between Assyrians and their Kurdish and Arab neighbors, especially that the oppression never stopped.

In 1933, the Simele massacre, led by General Bakr Sedqi, mirrored the horrific legacy of the 1915 massacre against minorities. By 2015, ISIS terrorist group continued this grim pattern of gradual attrition.

Massacres stories were passed down orally across generations, as Assyrians lacked the freedom of expression to document them. In the second half of the 20th century, following their mass migration to Western countries, they gained more freedom of expression to publicly share these stories through their descendants.

In the early 1970s, the Ba’ath government in Iraq tried to improve the status of Assyrians by enacting a law acknowledging their cultural and linguistic rights. Adad Youssef, head of the Alliance of Iraqi Minorities Network (AIM Network), noted in a conversation with Global Voices that, although the law was a step forward, it felt short. It recognized Assyrians as speakers of the Assyrian language, but not as an ethnic group, nor did it grant official recognition to the language. Nevertheless, this support helped preserve the language for a time.

The recognition of the rights of Assyrian speakers was far from the truth, as the Ba’ath Party categorized everyone as Arabs except Kurds and Turkmen. Nonetheless, this recognition enabled teaching Assyrian language in official schools in Assyrian-majority areas for many years until it stopped.

In the late 1970s, Saddam Hussein unleashed a campaign of oppression against his critics, including minorities such as the Kurds, Turkmen, Assyrians, and others. He stifled their expression of identity and Indigenous languages, wielding an iron fist over media and freedom of expression.

Under Hussein’s rule, an unusual dynamic unfolded for some minority groups, as noted by Assyrian activist Juliana Khamo. It was a social contract where Hussein offered a relatively comfortable standard of living in exchange for minorities refraining from exercising their freedom of expression. For Assyrians, this meant preserving their religious identity and language by remaining on the fringes of society.

But this delicate balance shifted with the American occupation of Iraq, which not only dismantled Hussein’s regime but also paved the way for the resurgence of militias and terrorist groups, most notably ISIS.

ISIS targeted Assyrian minorities among others, committing horrific atrocities against them. They destroyed churches, monasteries, and invaluable Assyrian cultural treasures, such as the ancient city of Nimrud, a vital archaeological site in the region.

Assyrians were coerced into converting to Islam, had their properties seized, and faced strict religious and linguistic restrictions. Assyrian women and girls, suffered repeated sexual violence and forced marriage. This reign of terror created a climate of fear, self-censorship, and silence.

ISIS extremist destroying Assyrian human headed winged bull statue in the Mosul Museum, Iraq, 26 February 2015. Sad, sad thing! NOOOOO! These monuments&sculptures belong to the whole humanity, they should be cherished and protected! Such a beauty, a real tragedy … #NeverAgain pic.twitter.com/vUx2yVjRDw

— Prehistoric Mojo (@PrehistoricMojo) February 27, 2018

The status of Assyrians’ freedom of expression in contemporary Iraq

Before ISIS emerged, significant developments regarding Assyrian’s freedom of expression in Iraq unfolded. In 2005, the Iraqi Constitution officially recognized the Assyrian language as a minority language, providing new opportunities for linguistic expression. Activist Adad Youssef says:

With the official adoption of the Assyrian language in Assyrian-majority areas, Assyrian education has flourished. Over 260 schools in Iraq now offer Assyrian, and the languages department at the University of Baghdad has established an Assyrian Language department.

Additionally, associations, clubs, and parties that publish material in both Assyrian and Arabic have been formed, covering a wide range of topics including religion, culture, politics, and education.

Constitutional recognition of Assyrian linguistic rights and technological progress has fueled optimism about Assyrian future. The digital age has equipped Assyrians with powerful tools to express themselves in their own language, and revitalize their mother tongue. Social media platforms, online forums, and Assyrian-language websites have become hubs for communication, content sharing, and cultural celebration.

Iraqi Assyrian journalist Khalpeel, detained by Kurdish troops in 2019, highlighted in a conversation with Global Voices that the Assyrian language gained support from iOS and Android mobile operating systems. A group of Assyrian youth is diligently working on integrating the Assyrian language into Google Translate. Khlapeel said:

Technology has been a tremendous asset for Assyrians, playing a pivotal role in revitalizing our cultural heritage. It has provided us with the means to use our language in the digital world. Today, Assyrians around the world can communicate using their own language.

Despite significant progress, freedom of expression in Iraq, especially for Assyrians remains grim, entangled in a broader context of fear, threats, violence, and persecution. In the World Press Freedom Index (WPFI) Iraq ranked 172 out of 180 countries in 2022.

In recent decades, Iraq’s Assyrians were forcibly moved to Kurdish-controlled areas, facing severe penalties for non-compliance. Despite constitutional guarantees of religious and linguistic freedoms, ongoing oppression, religious discrimination, and movement restrictions, have left them with little choice but to emigrate.