Q&A: Meet Fikri Ansori, Rejang language activist

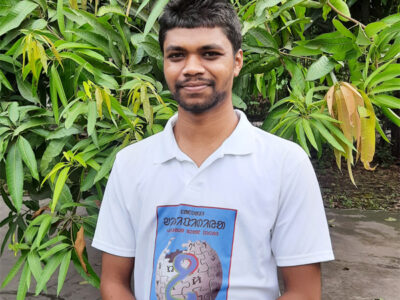

Language activist M. Fikri Ansori, hiking in the Sumatra rainforest. Photo provided by M. Fikri Ansori.

Following last year's successful social media campaign celebrating linguistic diversity online throughout Asia, the collaborative project is continuing in 2020. Every week, a different language activist and advocate will be taking turns managing the @AsiaLangsOnline Twitter account to share their experiences, best practices, and lessons learned from their revitalization work promoting the use of their native languages, with a special focus on the role of the internet. This campaign is a collaboration between Rising Voices, the Digital Empowerment Foundation, and the O Foundation.

Each week, the upcoming host will answer several questions about their background and give a brief overview of their language. This Q&A is with Fikri Ansori (@mfikriansori) who will provide a sneak preview of what he will be discussing during his week as host.

Rising Voices (RV): Please tell us about yourself.

Fikri Ansori (FA): I hail from Bengkulu, one of the poorest provinces in Indonesia. Due to derogatory terms that are often used to label us when we speak Rejang, I was very careful not to speak it and I didn't even want to have an accent in Malay (the lingua franca among many ethnicities) or Indonesian.

My Dad has long been ashamed of our language, but everything changed miraculously after I got accepted at Universitas Indonesia, one of the leading higher education institutions in the country. There, I built a huge network that changed me into who I am now. I re-learnt my native tongue and was able to master it in two years. This came as a bit of a shock to my family. One common reaction was to wonder how I could have travelled far away and mastered the Rejang language there.

Not only had I learnt the language, I chose to be its guardian, as it is one of many vernacular tongues across the archipelago that are endangered. I started my language activism through Wikipedia, mostly on the Indonesian version. I edited, enriched, and created many articles about my ethnicity. One fellow Wikipedian told me I could build a Wikipedia version in my language through Wikimedia Incubator. After that, I also got involved in managing the incubator. Even though we are seeing only a little progress for now, I still have hope.

Other than that, I tried to standardise Rejang orthography both in Roman script and in our own script, called Kaganga. Last but not least, I am now compiling words, terms, and newly coined idioms to create a contemporary dictionary. So, when I am not around anymore and the language is no longer in use, its words will still be contained in a book.

RV: What is the current status of your language on the internet and offline?

FA: Indonesia has only one national and official language, called Bahasa Indonesia (lit. Indonesian language), a standardised variety of Malay which was renamed after the country to add a nationalistic component. Apart from this one, we have no less than 300 other languages, called bahasa daerah, including my own language — Rejang. Thank God, some of these have a very large number of speakers and some of them have contributed a lot to the preservation of their language in this ever-changing environment.

Bahasa daerah are not protected yet, except for some municipalities that have a specific day to commemorate their local languages. Indonesian is monopolising almost every aspect of life: we watched films mostly in Indonesian, we read “Indonesian” books, and we were taught in school using Indonesian as the main medium of instruction.

Despite all this, Rejang is not dying, at least not in the foreseeable future. As it never became a lingua franca, it is exclusively used among people with close affinities like family members or best friends. Younger people in towns have already lost their ability to speak Rejang, but those who live in villages have successfully maintained their usage of the language. To safeguard this heritage, my local municipality (kabupaten) has made it mandatory to teach our language in grades 3-5 of elementary school. I really appreciated this.

Our people now use the internet in massive numbers, more than ever. Facebook is the most popular social media site and we have created our own spaces, where we speak almost exclusively in Rejang, exchanging ideas about our future, sharing our old recipes, traditions, and history. This is where Rejang is thriving today.

RV: What topics do you plan to focus on during the week that you’ll manage the @AsiaLangsOnline Twitter account?

FA: I actually do not have a plan yet. I want to talk, not only about the basic vocabularies and maybe dialectal differences, but also about facts regarding the Rejang language and its contemporary use, especially as it relates to online spaces. If I obtain permission, I would like to present my work on standardising Rejang’s orthography both in Roman script and Rejang script.

I've noticed that discussing basic vocabulary and dialectal differences easily attracts people's attention to our language, which is almost unknown outside Bengkulu. Indonesian netizens are particularly interested in vocabulary comparison between vernacular languages. For example, a house is called “rumah” in Indonesian, “bumi” in Sundanese, and “umêak” in Rejang language. I want to take advantage of this to capture my audience's attention.

As for facts and contemporary use, I aim to indirectly speak to fellow Rejang and pass the message that we should not belittle our language, though we are often stigmatised for speaking it. I want to show how we as younger people can present ourselves as guardians of our language. On this front, I would like my fellow Rejang to know that I've already contributed through the spelling standardisation effort. Now, I am challenging them to join in.

RV: What are the main motivations for your digital activism for your language? What are your hopes and dreams for your language?

FA: My biggest motivation is the fact that Rejang is my own language and heritage. If it is lost, I and the entire community will have lost our identity too. When nobody uses it anymore, its richness in particular fields, like our names for various kinds of mangoes (mangga, macang, kuini, plam, puak, tes, etc.) will cease to exist. It’s such a big disaster and unacceptable in my opinion. Now, everyone is online. The internet has come knocking on our door, both in villages and in talangs (settlements in plantations/farmland). Why not make use of it to prevent language decline?

I don't have grandiose or exaggerated hopes and dreams for my language, though. What I — as well as other Rejangs — want is for our younger brothers and sisters to use it exactly as we do now, like our ancestors did during their time. When we’re able to prevent the language from going out of usage, we'll be proud of what we have and thank God because we are Rejang. Then, derogatory terms will not matter anymore.

Support our work

Since Rising Voices launched in 2007, we’ve supported nearly 100 underrepresented communities through training, mentoring, microgrants and connections with peer networks. Our support has helped these groups develop bottom-up approaches to using technology and the internet to meet their needs and enhance their lives.

Please consider making a donation to help us continue this work.