Languages: Náhuatl and other languages according to its contributions

Yolitia is a Mexican electronic magazine. In the Náhuatl language, Yolitia means “reborn”. The initiative seeks to publish texts in different variants of Náhuatl and in other indigenous languages of Mexico. The journal consists of an editorial committee composed of 13 speakers of different Mesoamerican languages, all of whom are academics who have done studies in the social sciences; the languages represented in the editorial board are: Náhuatl, Náhuatl Pipil, Purépecha and Mixteco.

URL’s related to the project:

- Page: Yolitia

- Twitter: RevistaYolitia1

- Facebook Page: Revista Yolitia

Yolitia emerged in 2014, and has a direct precedent in the electronic magazine “Tonelhuayo”; both initiatives have had the participation and coordination of Victoriano de la Cruz, who is a researcher and a Náhuatl native speaker.

The project arises as a response to the lack of free materials in the Náhuatl language; it is intended to be disseminated not only in the community spaces, but also on global platforms for the sake of an internationalization of the language, which also contributes to the implementation of linguistic law to be expressed as a minority language in Mexican territory. Currently, the aim is to consolidate the editorial board through the formation of a civil association called “Tepoxteco”, in which the participation of representatives of different communities is expected.

Reception and Impact

The Indo-American communities and the Spanish monolingual population in Mexico are considered the main audience of the magazine. The objective of considering non-native speakers of Indo-American languages is to provide pieces in order to raise awareness for these groups faced with the linguistic diversity of contemporary societies. The link with this audience has been carried out from the Internet where they have distributed portable versions of the magazine, since magazines have been mainly used as didactic material.

One of the strategies to attract the public is to use the Facebook page of the project. They have also created a Twitter account. On YouTube, they also have a channel used for the distribution of audiovisual material related to the contents of Yolitia, and it’s also considered that later, these materials could also be subtitled in order to extend the audience.

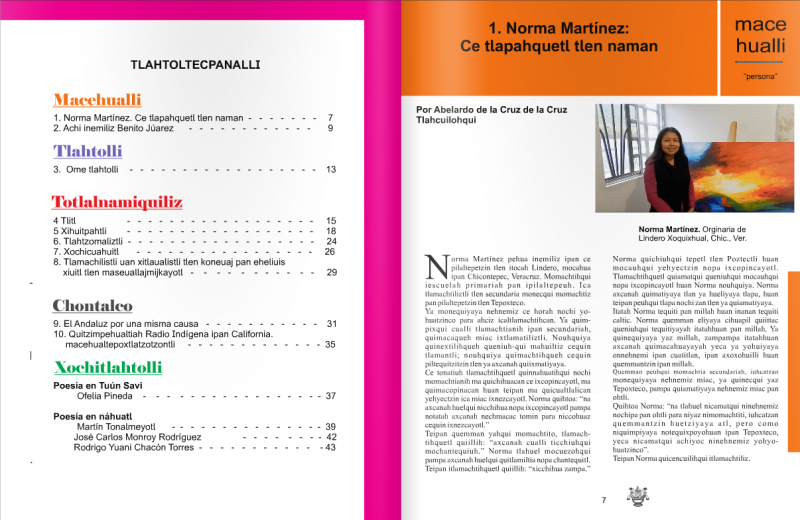

Example of the inside of the 1st issue of the Yolitia Magazine.

The Yolitia team has also sought links with the community spaces where Náhuatl is spoken. In this sense, it works directly with the community of Tepoxteco, in the municipality of Chicontepec in the Mexican state of Veracruz. The members of the community have been very enthusiastic about disseminating and making the presence of the local language visible. In this way, discussions have been given and material has been shared in schools ranging from preschool to high school, integrating the participation of parents, teachers, and general inhabitants of the community.

Software used: Movie Maker (Video editing), Corel Draw (Graphics layout), Texmaker (Text editing), Office Online (Office package).

Challenges and Limitations

One of the main challenges of Yolitia is the management of writing in the Náhuatl language since for the journal, it hasn’t generated a spelling standardization. For now, it is published using varying orthographic proposals. It is hoped that as people contribute material, a much more inclusive trend will be adopted in the spelling used. This situation becomes much more complex in that there is an increasing lack of educational proposals that encourage multilingualism, and with this, mechanisms for the production and distribution of bilingual materials can become possible.

The definition of the audience of the journal has also been presented as an aspect that has triggered multiple discussions. The team assumes that Yolitia writes for users of indigenous languages, which implies certain limitations, since the public are people who are studying and know Spanish and languages, mainly Náhuatl; however, the publication is not merely intended for an academic audience, but for the general public that is knowledgeable in languages. In this sense, it is hoped that as the project progresses, the type of audience that is reading the magazine can be identified.

On the other hand, the project does not yet have a committee to formally address legal and ethical issues related to content, which is why they have not published particularly strong or sensitive issues. There are sensitive issues that the team believes that if they are published, they should have special treatment and care, while at the same time, it has been decided that issues with a certain level of controversy such as drug trafficking or mining will not be addressed.

Long Term Goals

There are different range goals for this project: in the short term, in two years in particular, it is to have six magazine issues; in the medium term, it is to have an editorial that publishes in different indigenous languages; in the long term, it would be to consolidate diverse projects, to unite Nahua speakers and speakers of other languages to get along in research projects and lastly, as a main project, to create a university in Indo-American languages where knowledge can be disseminated by reflecting from its own language.

Victoriano believes that in Mexico, the original cultures are stereotyped and that it is necessary for people to raise their voices to express their own feelings, so that indigenous and non-indigenous people know what is happening in the country:

Nosotros somos los principales actores para defender nuestra ideología lingüística y cultural; no hay que esperar que otras culturas nos digan qué está pasando. Un indígena puede estar tanto en una ciudad como en una comunidad rural porque se siente parte de su tierra […]. Lo más importante es el respeto, no tolerar.

We are the main actors defending our linguistic and cultural ideology; let’s not wait for other cultures to tell us what is happening. An indigenous person can be both in a city and in a rural community because he feels a part of his land […]. The most important thing is respect, not tolerance.