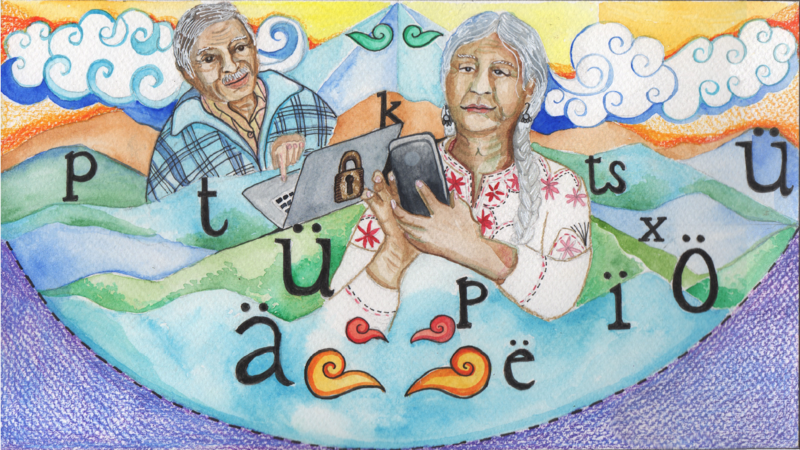

Illustration by Naandeyé García Villegas for Rising Voices

About

What are the challenges and needs for activists and their communities speaking Indigenous, marginalized, minoritized, or low-resource languages in regards to digital safety and security?

This is an overarching question that our team explored in regards language-related issues facing members of the Angika, Dagbani, Eastern Tharu, Gĩkũyũ, Kichwa, Igbo, IsiZulu, Kaqchikel, Mapudungun, Mixe, Odia, Sesotho, Torwali, Twi, Yorùbá, Yucatec Maya, Wayuunaiki, and Zapotec language communities.

For the past eight years, Rising Voices (RV), the digital inclusion arm of Global Voices, has been supporting language digital activists from Latin America, Africa, and Asia by facilitating spaces for peer learning, network building, training and mentoring, and amplification of their work. During this time, RV has gotten to know this network of language activists as they navigate through all types of linguistic, technical, socio-cultural, and political challenges. The need for information about safer and more secure communication channels and habits in their language communities has also been cited as a priority.

Language communities by region

Africa: Dagbani, Gĩkũyũ, Igbo, IsiZulu, Sesotho, Twi, Yorùbá

Asia: Angika, Eastern Tharu, Odia, Torwali

Latin America: Kichwa, Kaqchikel, Mapudungun, Mixe, Yucatec Maya, Wayuunaiki, Zapotec

This project made possible in part by support from the Open Technology Fund offered the opportunity for members of these language communities to begin exploring this intersection, but also the opportunity to identify needs, create recommendations, and set priorities in this space.

In early 2022, we invited 62 language activists from 62 different language communities from the extended RV network to share their current digital safety and security knowledge, attitudes, and practices, as well as their own initial perceptions about challenges facing their communities. Following the completion of that survey analysis, all 62 of the participants expressed an interest in being considered as one of the 18 case study researchers as part of the second phase of this project, highlighting the ongoing need for such exploration. Following an application process where the participants expressed their interest in participating further, 18 were ultimately invited to join the project team.

Working with researchers who come from the very language communities that were a part of this study was an essential element of this project. Not only do they have important knowledge about local context and preferences for approaches to information collection, but they are able to be in a better position to set priorities. They can act as trusted bridges between their local community and the wider digital safety and security networks.

The 18 case study researchers utilized a participatory case study research methodology that included online training regarding research design, field work, analysis, and report writing, and they were encouraged to choose the research questions on which to focus their work and the manner to collect and share the information. Following months of research, the researchers produced research reports that outlined their processes, their findings, and their analysis.

From those reports come the following 18 stories containing analysis that they decided to share to a wider audience, including testimonies from community members, reflections, and learnings that are also presented as recommendations for actions or strategies towards digital rights that take into account the diversity of languages.

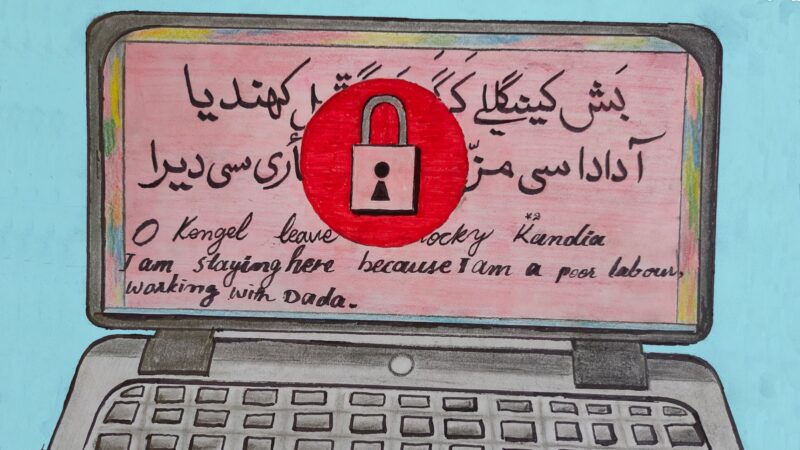

Each of these stories are available in Spanish, English, and each of the 18 languages that hold the knowledge and collective memory of these communities. They are the result of a flexible co-writing process with a project writer, and each which took different paths that are now reflected in the various shapes of the articles. Stories are accompanied by audio clips where researchers share their reflections from this research process, accompanied by an illustration created by an artist from the same language community.

These stories are now 18 windows to learn from the questions, needs and desires of these communities, where the relationship between digital rights and linguistic rights is fundamental and requires further action if we are to strive for a [digital] world that is safer for everybody.

Researchers

Project support team

- Ameya Nagarajan, Associate Editor

- Andrés Lombana-Bermudez, Lead Researcher

- Eddie Avila, Project Lead

- María Alvarez Malvido, Project Editor/Writer

- Mariam Abuadas, Project Management

- Nathaly Espitia-Díaz, Digital Security Advisor